- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

The Crimson Throne Page 3

The Crimson Throne Read online

Page 3

‘Not that the kind of Europeans found in Surat are much better,’ he continued. ‘They are but the riff-raff of our continent who drift into the Indies and, God knows, do not do Europe proud. Many of them try to smuggle goods past the customs when they land in Surat, especially gold, for which the idolaters have an insatiable appetite and which they hoard with an avarice that beggars imagination. The English are the worst. When they adopted from Europe the fashion of wearing wigs, they came up with the ingenious notion of concealing Jacobuses, rose-nobles and ducats in the nets of their wigs every time they left their vessels to go ashore. Emperor Shah Jahan looks indulgently on attempts at smuggling, viewing it as a game of ingenuity between the smugglers and his officials. Anyone caught smuggling merely pays ten instead of the normal five per cent duty on the goods. Because of the kind of European who makes his way into India, the whole continent has got a bad reputation among upper-class Indians as home to a dishonest people lacking finer sensibilities and impelled solely by greed and avarice.’

As my strength returned, my carriage rides became more frequent. In the evening, before the sun had set and a cool breeze began to come up the river from the sea, I would alight on the quay to take in the air on the bank of the river that was crowded with ships and innumerable small boats racing up and down on the sweet water. Ships from far-off regions of the world—Europe, Persia, Arabia, Basra, Siam, Acheen, Malacca, Batavia, Manila, China—as also from Malabar and Bengal in the Indies, seemed to be regular arrivals at the country’s busiest port.

‘The first teacher of my body and the two teachers of my mind’

NICCOLAO MANUCCI

TO THIS DAY I do not know why Luigi chose me as his friend—as much as permitted by the disparity in our ages, of course—since he determinedly avoided other Europeans. I suspected his avoidance was due to an odd physical deformity of which he was acutely self-conscious. Luigi’s arms were at least a foot longer than others’ and, when he stood, they descended below his knees. With thick red hair that hung low on his forehead and covered the back of his neck, a furry beard that hid most of his face, and a distinctive hunch, he resembled a Barbary ape when he walked.

Luigi was one of those people whose natures totally belie their appearance. Behind his shy smile and a mouthful of crooked yellowing teeth hid the gentlest of hearts. In all the time I knew him, I never heard him speak ill of any man, as if years of ministering to the sick and the poor had erased his ability to make judgements. His voice, strangled in normal conversation, rarely more than a mutter, took wing when he retreated to a corner of the convent’s garden in the evening to sing, mainly to himself. The song he sang was always the same: St Francis’s haunting hymn:

“Dolce sentiré come nel mio cuore

Oraumilmcnte sta nascendo amore.

Dolce capirc Che non son’più solo

Ma Che son’parte di una immensa vita

Chegenerosa risplendeintorno a me:

donodi Lui del suo immenso amore.’

(‘Sweet it is to feel how, in my heart,

Now, humbly, love is being born.

Sweet it is to understand, that I am no longer alone.

But that I am part of an immense life

That, generously, shines around me,

Gift of Him, of His immense love.’)

Many a time, on my way out to a tavern or my favourite brothel at dusk, when lamps were being lit and the monks were busy with their chores before the dinner bell was rung, I would stand behind the oleander bushes a few yards from the stone bench on which Luigi sat, plucking on his guitar, and listen to the saint’s love for God and His creation come pouring out in Luigi’s sweet tenor. I could feel the long-buried innocence of my soul seep into my heart as I walked out of the gate, on my way to assuage the cravings of a young man’s body. I felt no shame, no guilt. Indeed, it was as though St Francis himself was blessing the urgings of my flesh.

Luigi was wholly given to God’s work which, to him, culminated in healing the sick. He would disappear, sometimes for weeks, into the interiors of the country with a horse that carried supplies of drugs and instruments. (In India, the profession of the apothecary is unknown. A doctor must prepare his own medicines and ointments). Whenever he was called upon to treat a sick infant or one on point of death, he would first sprinkle it with the water of baptism. ‘In the eight years I have been here, I must have baptized over fifteen thousand infants,’ he told me once we had become friends. ‘Now, when I go into their villages, mothers think that sprinkling water on a sick child is part of the treatment.’

Many Hindus, a gentle but excessively superstitious race as I was soon to discover, prostrated themselves on the street when Luigi passed by. One of their most revered gods is the monkey-god, who is also their god of healing. Given his appearance and calling, their obeisance to Luigi was more comprehensible but no less ludicrous. Naturally, to the Inquisition, the whole affair smelt of heresy. I remember how Luigi’s voice had quivered as he told me of the time he was summoned before the tribunal. No one takes such summons lightly. It produces fear and trembling even in the most intrepid of men. More than three thousand men and women have spent years in the dungeons under the floor of the hall, where the tribunal meets, merely on grounds of suspicion. Those pronounced guilty of heresy were routinely burnt at the stake in the square in front of the Se Primacial, the Cathedral of St Catherine. Those who confessed their guilt were mercifully strangled before the pyre was lit.

I could imagine Luigi shuffling forward, his accursed arms swinging clumsily before him as he was called before the bench. I could feel the terror he tried to conceal while the tribunal conferred—and the surprise on his face as the Inquisition pronounced its verdict. Luigi’s punishment was unique: whenever a Hindu prostrated himself before Luigi, the priest was to mirror the action. No one had ever suspected that the Inquisition had a sense of humour! The nature of Luigi’s punishment was one of the compelling reasons that kept him within the four walls of the convent whenever he was in Goa. That his trial was so short was almost certainly due to his lack of worldly goods, of the gold, silver and jewels the Holy Tribunal regularly confiscates to defray its expenses.

In spite of his ordeal, Luigi did not harbour any ill will towards the Inquisition. Years of intercourse with Hindus, especially the Hindu doctor who was also to become my teacher, had infused his already gentle nature with a mildness that I did not appreciate at the time. I even thought of it as unmanly. I had not received any formal education in my youth but in the year I spent in Goa under Luigi’s guidance I acquired the kind of education I would never have got at the best European universities. It was Luigi who advised me to seek work in the Royal Hospital of Goa as an orderly.

‘You have no trade, Niccolao, but all the needs of a young man. To satisfy those needs you will require money,’ Luigi had smiled, hinting at the money it would cost me to visit even the cheaper brothels.

Like the rest of Goa, the Royal Hospital, once renowned all over India, had fallen on bad days. Patient care had deteriorated, as had cleanliness and the quality of medical equipment. The orderlies, mostly of mixed breed, supplemented their income by extorting money from the patients for the smallest service—giving a thirsty patient a glass of water, for instance. The food, beef tea and rice with an occasional ragout, which the orderlies shared with the patients, was terrible. But the hospital still had some expert surgeons and the year I spent there gave me the opportunity to study hundreds of patients and a variety of sicknesses from the closest quarters.

Between Luigi’s careful explanations and instructions, and watching the experts at the Royal Hospital closely as they went about their daily duties, I soon mastered the routine medical procedures. I did not much care for purging. It was too easy. What skill is required in cleaning a patient’s system by giving him large doses of Calomel that makes him incontinent from the mouth and the anus? Cauterizing, searing a bleeding part of the body with a hot iron or boiling oil to stop the flow of blood, did n

ot need elaboration either. Blistering, the pouring of acid or application of hot plasters on the skin to raise blisters, which would then be drained, was more mysterious. ‘The body can only contain one illness at a time,’ Luigi had explained. ‘When a second illness enters the body, the first one is expelled. The burn on the sick person’s body forces out the original illness.’

I avoided both these procedures as much as I could. They were too violent for my peaceable Venetian nature. As was the treatment of serious illnesses such as malaria and cholera, commonplace in Goa because of its pestilential climate, by pressing a red-hot iron rod against the middle of the heel, which allays the stomach pain and stops the vomiting and other discharges. I could never get used to the smell of burning skin and the patients’ screams of pain. The treatment that I adopted as my own, and which later stood me in good stead in my practice at the Mogul court, was bleeding.

Goan doctors, who have incorporated some Hindu notions and remedies in their practice, are famous all over the Indies as experts in this highly sought-after therapy. Impure blood is the root cause of many ailments and the process of bloodletting that rids it of poisons is not only recommended for fevers and inflammations but also in instances of stubborn skin diseases, tumours, gout, excessive drowsiness, and when the liver and spleen become enlarged. I remember I was fascinated by the treatment the very first time I watched one of the surgeons at the hospital, a mestica with a pockmarked face and smelling of feni, the palm liquor he drank in large quantities, carry out the procedure. As the attending orderly, he had asked me to take the patient, an attractive thirty-year-old woman of his own race, out into the hospital garden and make her stand in the sun for half an hour so as to make the blood flow easily. I could not but admire the extreme care with which the surgeon, none the worse for his alcoholic excesses of the previous night, first applied an antiseptic paste and then used a sharp scalpel to make superficial incisions in selected places on the woman’s arm. After each incision, he examined the blood that he collected in a shallow pan. He must have made at least twenty parallel or vertical incisions on the woman’s arms before he was satisfied that the dark, poisonous blood had been replaced by healthy blood, fighter in colour. I had marvelled at the doctor’s technique. Not only had the woman shown no sign of pain but the cuts he had made had been so precise that the blood that collected in the pan was never more than 350 ml. To me, bloodletting was like the delicate work of a goldsmith, far superior to the blacksmithy of cauterizing and blistering.

Soon I too became proficient in the art by practising on patients who were mostly too sick or too poor to know the difference between an orderly and a real doctor. In return, I was much kinder to patients than most other orderlies who took money for the simplest of favours like bringing them water or sneaking them some confectionery. I never took money from patients, even when I helped those convalescing from bloodletting avoid drinking the three glasses of cow’s urine that the hospital prescribed as mandatory. This was another remedy learnt from Hindu doctors who ascribe medical benefits to the five products of the cow—milk, curd, clarified butter, dung and urine. Whether in exchange of money or not, we orderlies emptied the glasses on the floor and the hospital always stank of cow urine.

As our friendship deepened, I discovered that Luigi was also a firm believer in Hindu medicine though he was ever so guarded when he talked of it.

Their medicine is very different from ours,’ Luigi would say, initially feigning condescension. ‘In their view, the sovereign remedy for sickness is abstinence. A patient with a fever should not be given any nourishment. Nothing is considered worse for a sick body than meat broth. They believe it corrupts the stomach and worsens the illness. But most extraordinary is their conviction that bloodletting should be employed sparingly and only in extraordinary circumstances. It is recommended only when an inflammation of the chest, liver or kidneys has taken place.’

Gradually, as our friendship progressed, I discovered that Luigi’s fascination for Hindu medicine had developed from his intimacy with a Hindu physician who lived in a remote village almost halfway to the border of the lands ruled by the Marathas and whom Luigi sought out whenever he travelled in those parts. His association with the Hindu doctor, whom he respectfully called Vaidraj—king of physicians—went back fifteen years. He had kept it secret so as not to be misunderstood by his Franciscan brothers. Or, worse, by the Inquisition.

‘More so,’ he said hesitatingly, ‘because I fear he combines medicine with witchcraft.’

‘Witchcraft?’ I asked.

‘I have seen him perform marvellous feats of diagnosis by just feeling the pulse in a patient’s wrist. An experienced physician, Vaidraj tells me, can see the image of every important organ of the body reflected in the beat, movement and temperature of the pulse. But what is more astonishing—and that is where I suspect the involvement of witchcraft—is that in case of a longstanding illness, he can predict the time of the patient’s death to a precise number of days or even hours.’

I was fascinated by what Luigi told me. I promised myself that one day I, too, would master the Hindu art of reading the pulse, even if it be witchcraft.

‘His medicine possesses many other secrets,’ Luigi continued. ‘Even Mohammedan physicians at the Mogul court, followers of the rules of Avicenna and Averroes, who, like the rest of their race, generally despise the Hindus, are not averse to including some of the Hindu remedies and methods into their own practice.’

I now understood why Hindu doctors were so well regarded in Goa, even by the Portuguese. They were the rare heathens allowed to walk on the street under umbrellas carried by servants although they continued to be denied the privilege of wearing shoes. The sight of a famous physician walking barefoot while dressed in magnificent robes, followed by servants holding a richly caparisoned umbrella above him, the dignified expression on his face denying the truth revealed by his bare feet, always evoked in me a strange mix of outrage and admiration.

It was the word ‘secret’ that became lodged in my mind like a hook in the mouth of a fish. If I wanted to consort with nobles and princes in the capital of the Mogul empire, be remunerated in purses filled with gold mohurs and pearl necklaces, in place of the few silver coins reluctantly forked out by ordinary citizens for medical attention, then I needed to know the secret remedies of the vaids that were still hidden from my Mohammedan and European colleagues and rivals. I began to pester Luigi to take me to meet Vaidraj. I had been in Goa for about nine months when Luigi finally agreed.

Vaidraj’s village was no more than fifteen kilometres inland but it still took us the best part of a day to reach our destination. First, we travelled upstream for a couple of hours along a narrow channel that cut through a thick undergrowth of dark green mangroves which had been never penetrated by rays of the sun. Then we walked across a gently undulating plain dotted with paddy fields in all shades of brown, patiently awaiting the monsoon showers still five months away. Carefully tended groves of trees announced the existence of a few villages much before we caught a glimpse of human habitation.

Situated at the foot of a small hill, the doctor’s village was larger than I had expected. Rows of mud huts with thatched roofs made from dried palm fronds, which one sees all over Goa, were broken by the occasional stone-and-mortar house with tiled roofs. A small but lively bazaar had been constructed at the centre. Almost all the vendors, squatting in the shade of torn umbrellas, their wares spread in front of them on mats woven from coconut fronds, were women. On sale were mounds of dried ginger, tamarind, lentils, jaggery, areca nuts, bunches of small yellow bananas, papayas, jars of sesame oil. Clad in red or green saris that were tied with one end pulled between the thighs and secured at the lower back and short-sleeved bodices that ended above the waist, the women gossiped loudly among themselves as they bargained with customers. In its animated, amiable chaos, though not in its skimpy offerings, the bazaar reminded me of markets in Venice.

We made our way past the bazaa

r to the far end of the village where Vaidraj was awaiting our arrival in the freshly swept forecourt of his hut. A basil plant, considered holy by the Hindus, had been planted in the middle of the courtyard. A step or two higher than the yard was a veranda that ran along the entire width of the house. In one corner of the yard, freshly plucked red chillies had been laid out to dry in the sun. In another corner, next to a well, was a raised mud platform under a peepul tree. This was to be our dwelling for the two days of our visit. At night, thin mattresses spread on the platform served as our beds. These were rolled up in the morning. During the day this is where we sat and spoke with Luigi’s friend and where our meals were brought to us on plantain leaves.

Vaidraj’s black eyes were sharp and shrewd and I could feel their scrutinizing gaze bore into me before they softened in affection as he welcomed Luigi with folded palms. As we took our seats on the platform under the peepul tree, two servants came out of the house. One carried tumblers of milky coconut water as refreshment for our dry throats. The other brought a bucket of water from the well to wash our dusty feet.

I took an instant liking to the doctor. As Vaidraj spoke to Luigi, enquiring after his health and the state of affairs in Goa, his dark eyes often turned to look upon my face. I realized why Luigi, otherwise a recluse, had warmed to him. A small, lean man in his early fifties, with close-cropped grey hair and grey stubble on his unlined cheeks, Vaidraj was dressed simply in a white cloth wrapped around his waist which came down to his knees. Except for a white cotton string looped across his torso, a sign that he had been born into a high caste, he was bare-chested. When Luigi introduced me and spoke affectionately of my dreams of making my fortune at the court of the Great Mogul, Vaidraj asked me in halting Portuguese whether I spoke Konkani, the local language. I answered in the affirmative in his own tongue and his face broke into a child-like smile. He turned to Luigi and, patting him on the shoulder, said, ‘You have taught him well, my friend.’ Then he turned to me. You want to learn about our medicine, my friend tells me.’

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

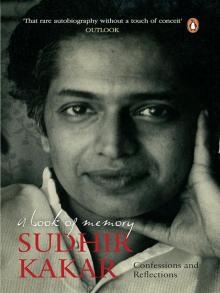

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory