- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

Death and Dying

Death and Dying Read online

Sudhir Kakar

DEATH AND DYING

Contents

By the Same Author

Dedication

Introduction

Foreword to the Series ‘Boundaries of Consciousness’

Survival of Bodily Death

Plato’s Phaedo and the Near-Death Experience: Survival Research and Self-Transformation

‘Sorrow More Beautiful than Beauty’s Self’: John Keats and the Music of Mortality

Death and Afterdeath in the Writings of Rabindranath Tagore

Jung’s Near-Death Experience and Its Wider Implications

Goodbye and Good Mourning

Symbolizing a Definitive Absence—A Psychoanalytic Reflection on Death and Dying

Celebration of Death: A Jain Tradition of Liberating the Soul by Fasting Oneself to Death (Santhara)

Adding Life to the Dying: Palliative Care and Psycho-Oncology

Contributors

References

Notes

Footnotes

Symbolizing a Definitive Absence—A Psychoanalytic Reflection on Death and Dying

Read More

Follow Penguin

Copyright

By the Same Author

ALSO IN THE SERIES

On Dreams and Dreaming

Seriously Strange: Thinking Anew about Psychical Experiences

For Renate Poggendorf,

a woman of courage and integrity

Introduction

Sudhir Kakar

What do we talk about when we talk about death? Whether we articulate it clearly or approach it through indirection, we are talking of the dread as we contemplate the inevitable ending to life. We are talking of our imaginings of afterdeath, the presence of an afterlife for those strong in their religious faith, but as extinction for those who lack or have chosen to forswear the consolations of traditional religions. We are talking of mourning, the grief evoked by this mysterious event that cruelly snatches away people we have dearly loved.

Objectively, death is not mysterious. Its advent is marked by the stoppage of respiration and heartbeat, drop in body temperature, cessation of all brain activity and the beginning of a process of decomposition. The mystery of death lies elsewhere. Although billions have gone to their deaths in the thousands of years since human beings first developed language, we do not have a single, credible account of the subjective experience of dying and afterlife. People can only talk of these from their imaginings, the imagination influenced by their religious and cultural traditions and their own experiences of the death of others. In other words, to use the philosopher Richard Wollheim’s distinction, human beings are fated to explore death only from a peripheral and never a central vision.

Our awareness of our own death is at the level of thought, not emotional conviction. We are capable of thinking of our death, but incapable of imagining it. In the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata, there is a story of a series of questions the god of justice and morality, Dharma, disguised as a yaksha, a nature spirit, asks the eldest of the five Pandava brothers, Yudhishthira, who has come to an enchanted lake in which his four brothers have found a watery grave. Impelled by a raging thirst, the brothers did not heed the yaksha’s warning not to drink the water before answering his questions. Yudhishthira is more patient and agrees to the yaksha’s stipulation. His answer to one of the yaksha’s last questions on what is the most amazing thing in the world—’Day after day, countless creatures are going to the abode of Yama (the god of death), yet, those that remain behind believe themselves to be immortal. What can be more amazing than this?’—remains true for all times and cultures. As far as the unimaginability of death is concerned, there is little difference between Yudhishthira’s north India of 600 bce, the time of the Mahabharata, and central Europe of the early 20th century where Freud writes:

It is indeed impossible to imagine our own death; and whenever we attempt to do so we can perceive that we are in fact still present as spectators. Hence the psychoanalytic school could venture on the assertion that at bottom no one believes in his own death, or, to put the same thing in another way, that in the unconscious, every one of us is convinced of his own immortality.

Unable to imagine our own deaths, fated to be spectators at the death of others that keep reminding us that our life too is finite, this volume invites the reader to engage with the major issues raised by the the unimaginable: dying, afterdeath and mourning.

Three of our contributors, on the forefront of consciousness research, explore the objective evidence for an afterlife, an issue that has fascinated the human mind as long as it has been conscious of mortality. In their essay, Emily and Edward Kelly question two basic assumptions of the contemporary discourse on survival after death. The first assumption is from the biological and neurosciences which, from the strong evidence that correlates mind and brain, reaches the conclusion that the death of the brain is the end of consciousness and personhood. The other assumption is of the world’s religious traditions that look at survival after death as a matter of faith. Here, concerns around credible evidence that supports doctrines are viewed as both irreverent and irrelevant. The Kellys marshal impressive, still little-known empirical evidence to question both the contemporary scientific and the traditional religious assumptions on survival after death. They then present an alternative interpretation of this evidence, which brings together the strengths of both science and religion, to a question whose answer is crucial to the way we choose to lead our lives.

Michael Grosso’s essay, focusing on the near-death experiences of persons who exhibit a loss of all brain function during a cardiac arrest, is on the implications of the presence of a heightened consciousness during such experiences when, from the viewpoint of the neurobiological model, there should be no consciousness at all. In a stimulating discussion he looks at these experiences, and consciousness research in general, in light of some of Plato’s ideas—the archetype of the ‘substantial’ soul, philosophy as a ‘practice of death’, and the very different way the world appears in a lucid, ‘aitheric’ light rather than our normal dull, ‘misty’ perception of its features.

From the empirical evidence of consciousness research, we turn to another kind of ‘evidence’: the writings of three extraordinarily creative individuals, the English poet John Keats, the Indian poet and painter Rabindranath Tagore, and the great Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung.

To come to the poets first, often the forerunners of psychologists and certainly much better communicators of their insights, the theme of death is next only to that of love, which pervades some of the world’s best literature.

In his insightful contribution, Ronald Sharp explores the paradox in Keats’s work, that a sense of mortality deepens one’s appreciation of beauty, and that life accrues value precisely to the extent that one intensely experiences its fragility and transience. Although Keats discovers in the depths of suffering the most persuasive grounds for affirming life, such affirmations can never fully protect him from the sorrows of loss. But by embracing mortality—not just passively accepting or stoically resigning himself to it—Keats discovers that autumn has its own music, which is even more beautiful than that of spring, more beautiful, as he says in ‘Hyperion’, than ‘Beauty’s self’.

Like Keats’s early experiences of death—of his father, mother and brother—Rabindranath Tagore also ascribes the transformation of his perspective on life and his view of the world to the sudden death of a deeply beloved person. In the dark depths of his mourning, he glimpsed flashes of joy. Death became a theme he returned to again and again in his poetry and other writings. The fear of death that lies in the emptying of the self, of the self stripped of all memories and desires, Tagore maintained, was a transi

ent phenomenon. Death was the opposite of birth, not of life of the self. Life and death are twin brothers that serve the purpose of the evolution of the self. The darkness of death has the light of a greater self hidden in its folds that reveals itself in afterdeath.

John Dourley guides us through C.G. Jung’s thoughts on death and afterdeath, both preceding and following Jung’s own near-death experience, when, in a state of delirium after a heart attack, he had a number of visions. Jung’s main argument is that the deeper human psyche, which he calls ‘primal form’ is beyond death even in the face of death, and that to live a life of meaning is to connect with this dimension of the psyche in life itself. Like Tagore’s ‘self’, Jung’s primal form is, so to speak, a manifestation of the psyche’s overriding movement towards the spirit. For Jung, the psyche and soma are integrated in death in an intense burst of concentrated, spiritual energy. It is perhaps the residue of the material in the spiritual which underlies the mystical and poetical visions of death and its aftermath (such as those of Tagore) as a movement towards an intense energy of light. Dourley also discusses other aspects of Jung’s thoughts on death, such as the possibility of communication between the living and the dead, not in the realm of the supernatural but that of the psyche, and the psychology of the realization of the primal form in the mystics to whom Jung felt drawn.

The two essays by Patrick Mahony and Eckhard Frick address an issue of vital import to the living in their relation to the dead: mourning, pithily described by the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips as ‘the necessary suffering that makes more life possible’. Mahony observes that the crucial events of dying and death raise many questions of grand psychoanalytic interest, ranging from the fear of death as primary or secondary, the effectiveness of wisdom in the acceptance of death, and the scope of healthy and pathological mourning. Four vignettes of two Buddhist monks, the Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, and the atheist Freud offer other pertinent considerations about the impact of death. Finally, the frequent idealization of Freud is given as another example of malignant mourning.

In his essay, Ekhard Frick observes that mourning is not limited to bereaved persons but also concerns dying persons and, in a broader sense, our whole symbolic life which is playful coping with a rhythm of absence and presence. The dying and the bereaved persons’ mourning processes open a spiritual realm, connecting individual grief to the archetypal mourning and its collective symbols, the archetypal layer first represented to us by the mother as first incarnation of world and Self.

The volume ends with two essays on the process of dying. Katharina Poggendorf-Kakar explores the affirmation of death in santhara, a ritual fasting to death in the Jaina tradition of India. Monks, nuns and laypeople alike choose santhara in the hope of liberating their soul (jiva) from the cycles of rebirth. In this radically ascetic religion, santhara is a process of shutting down the body without fear, while keeping the mind awake till the end.

Pia Heußner and Almuth Sellschopp take us into the territory of palliative care for the dying, a new discipline where the quality of life in the time left for the dying is given more importance than the sheer extension of lifespan at all costs. Focusing on patients dying of cancer, they plead for psycho-oncology and the need for psycho-oncological competence within Palliative Care teams.

Foreword to the Series ‘Boundaries of Consciousness’

After On Dreams and Dreaming and Seriously Strange, Death and Dying is the third volume of the series on ‘Boundaries of Consciousness’, which explores the uncharted territory at the edge of our current psychological knowledge. Some of this territory extends into what has been called the sacred, and scholars of religious studies and philosophers are as much a part of these conversations as are psychologists, psychoanalysts and neuroscientists. The present volume is the fruit of a symposium held at Wasan Island on Lake Muskoka in Ontario, Canada, in August 2011. Wasan Island is, for me, a special place where people who want to interact without distractions can meet and learn from each other. A heart-shaped island covered with trees, in the middle of Lake Muskoka, it lends itself to being a retreat for groups who want to venture into new experiences as well as into an exciting group process.

Wasan Island protects and inspires such learning processes which take place between creative opening and concentrated cooperation; between an ambitious orientation on results and a group dynamic which is typical of the island. For ten years now, the Breuninger Foundation has invited personalities from science, industry, culture and international organizations to Wasan Island during the summer months.

In 2008, we began, with Sudhir Kakar and Almuth Sellschopp, a series of meetings bringing together individuals with high academic reputations in the fields of theology, philosophy, medicine, history and psychotherapy. The intention was to give them the opportunity to present their latest fndings from their areas of expertise, to discuss them critically in a protected space, and to locate the fndings within a wider, public context.

This concern goes back to my father, the founder of the Foundation, Heinz Breuninger, a man who was a model of openness in dialogue and a readiness to get involved, without prejudice, in contradictions.

His main focus was universal history, and under the direction of Rolf Peter Sieferle the Breuninger Foundation has made a name for itself with the ‘Europäischen Sonderweg’—European Special Way.

I try to connect my personal scientific upbringing and studies as an economist and psychologist, my socialization within a business family and my situation as a European, to my many years of spiritual experience—the practice of yoga and meditation, and an intense intellectual engagement with Eastern philosophies—without getting stuck in esotericism.

The meetings are not only about a high-level, detailed imparting of knowledge but also about embedding this knowledge in a dialogue within a small circle: a shared search for ways between difference of views (diversity) and commonness within a framework whose format differs markedly from most academic events. Whereas most academic seminars are concerned with approval or rejection, the differences between positions in the Wasan conversations are valued, and controversial viewpoints and dissent are expected to have space to develop.

Wasan Island can, then, be understood as an ‘experimental field’ in which—as in the following report on the dream seminar—timeless and contemporary, Western and Eastern views of the truth (a defnite logic as against the acknowledgement of contradictions) meet.

Thanks to its unique spiritual strength, stemming from its indigenous American Indian past, Wasan Island is particularly suitable as a location for this project. To this is added a boundary situation which originates from the island itself: its spatial configuration, and a fixed time frame. Paradoxically perhaps, this allows an opening, a movement towards unity, a step beyond the borders of individuality and autonomy. The processes of the symposiums allow the participants to present their position authentically and without fear, to engage with the position of the other without prejudice and without evaluation, and without the feeling that dissent will be edged out. This results in a very fruitful learning climate.

Two important elements of the Wasan conversations should be mentioned: on the one hand, it regularly happens during the course of the symposium that ‘world-famous’ scientists from widely different fields become people who display an interest in dialogue beyond their immediate presentation, and who use the island situation with its various opportunities—at the dock, at dinner, and afterwards—to carry their discussions further. This experience makes the Wasan offer of free spaces outside the formal meetings, in groups and among individuals, so important.

Another element is the transfer which takes place, often of very complicated experiences, ‘back into the world’. This transfer should, in the understanding of the Foundation, be commensurate with the outcome of the event and its capacity to apprehend reality—always with the ‘humanistic chance’ of returning to Wasan Island to assimilate the continually developing process of understanding experience

, and to continue the dialogue.

The project, ‘Boundaries of Consciousness’, with Sudhir Kakar as project leader, comprises four successive seminars. His personality embodies a style of leadership which has the courage, liveliness and spontaneity to look for new balances between psyche and spirituality, and thereby to protect boundaries and construct barriers in the face of potential abysses. Gently sensitive, I see him as an experienced mountain-guide on the glaciers of new psycho-spiritual territory, focused on bringing into awareness the barriers of consciousness between subject and object, opposite and yet related, and always aware of the crevasses that lie in wait for the unwary.

My wish is for the reader to encounter the individual contributions with the same curiosity, openness and tolerance that are such a feature of the conference atmosphere on Wasan Island.

Helga Breuninger

Survival of Bodily Death

Emily Williams Kelly and Edward F. Kelly

Simply present the words ‘death’ and ‘dying’ to a group of people, and you will undoubtedly get a wide variety of responses—as evidenced by the wide range of topics and approaches that participants in this conference came up with when presented with these words. Many responses deal, in one way or another, with basic questions that all thinking human beings ask themselves at one time or another: What does death imply about the meaning—if any—of life? How do I best live in light of my inevitable death? How do I deal with grief and loss? What is a ‘good’ death? And how do I attain it?

Lurking behind all such questions, however, is the most basic of all: Do we, in some manner, continue to exist after physical death, or are we extinguished? Answers to all the above questions depend heavily on how one answers this one. And here we find ourselves on the horns of a dilemma—one that has been emerging for centuries, but has now, in light of the immense progress of Western science in the last century or so, reached critical proportions. The great religious traditions have taught survival after death, in one form or another, as a major tenet of their faith. But modern science, particularly biology and neuroscience, has been amassing ever greater amounts of evidence confirming what we all observe every day—that our mental life or state of consciousness depends intimately on the state of our brain and body. The conclusion that many modern observers, scientists as well as others have come to is that when the brain dies, so must the mind.

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

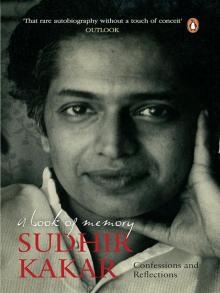

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory