- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

Indian Identity

Indian Identity Read online

SUDHIR KAKAR

Indian Identity

Intimate Relations

The Analyst and the Mystic

The Colours of Violence

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

About the Author

1. A Personal Introduction

2. Intimate Relations

3. The Analyst and the Mystic

4. The Colours of Violence

5. Notes

6. A Note from the Author

PENGUIN BOOKS

INDIAN IDENTITY

An internationally renowned psychoanalyst and writer, Sudhir Kakar has been a visiting professor at the universities of Chicago, Harvard, McGill, Melbourne, Hawaii and Vienna, and a Fellow at the Institutes of Advanced Study, Princeton and Berlin. Currently, he is Adjunct Professor of Leadership at INSEAD in Fontainbleau, France. His many honours include the Bhabha, Nehru and National Fellowships in India, the Kardiner Award of Columbia University, the Boyer Prize for Psychological Anthropology of the American Anthropological Association, and Germany’s Goethe Medal. The leading French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur listed him as one of twenty-five major thinkers of the world.

Sudhir Kakar’s books, both non-fiction and fiction, have been translated into twenty languages. His non-fiction works include The Indians: Portrait of a People; The Inner World: A Psychoanalytical Study of Childhood and Society in India; Intimate Relations: Exploring Indian Sexuality; The Analyst and the Mystic: Psychoanalytic Reflections on Religion and Mysticism and The Colours of Violence. His three published novels are The Ascetic of Desire, Ecstasy and Mira and the Mahatma. He has also translated (with Wendy Doniger) Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra.

To the memory of Erik H. Erikson, shared with my two dear friends,

John Ross and Pamela Daniels.

A Personal Introduction

In the memories of my childhood, the season is always summer. Blazing hot, dry, and invariably dusty, it is the special summer of small district towns in West Punjab, an area that now lies in Pakistan. Each of the towns—Dera Ghazi Khan, Multan, Lyallpur, Sargodha—where we would live for two to three years before my father was transferred to another town, indistinguishable from the one we had just left, have coalesced in my memory into one quintessential town. This is a town without character, neither old nor new, and no one is interested in its past history or its future prospects. Through the nostalgic haze of childhood, I can still summon up images of the town’s cheerful dirtiness: its narrow, crowded bazaars lined with open, flowing gutters carrying children’s pee, vegetable peelings and eggshells bobbing on the surface of the inky-black water. I can see the flies clustering on mounds of raw brown sugar in eating places where the chipped enamel plates with their blue borders are never clean enough and the smell of fried onions, garlic, cardamom, cloves and turmeric is embedded in the very walls.

The town is also the central market for surrounding villages. After the harvest, ox-carts loaded with gunny bags full of wheat or stacked high with sugarcane stream in. Their arrival is announced by the chiming of small bells that hang around the necks of the oxen drawing the cart, placidly ignoring the mangy, yelping dogs’ attempts to provoke them. On market days the farmers are accompanied by their gaily-dressed women and excited children, giving the drab town a touch of shy festivity. These large family groups move deliberately from one shop to another, looking at the wares without expression, unhurriedly bargaining for their small luxuries—coloured glass bangles for the women, a piece of cloth for a child’s shirt, a burnished copper pot and brass tumblers for the family kitchen.

As a child, I was as much an outsider to the bazaars as any child from the village. We lived a couple of miles away from the heart of the town in what was called the Civil Lines. The Civil Lines and its military counterpart, the Cantonment, were to be found in many towns. They were creations of the British whose rule was approaching its end in the period of which I write, the early 1940s. The houses in the Civil Lines, built at the end of the last century, were sprawling single-storeyed affairs with acres of ground and a number of servants’ quarters. Lawns and flower beds, a vegetable garden, a pond or a well, groves of fruit-bearing trees (I particularly remember the blood-red oranges of the grove in Sargodha), were often a part of the estate. Not many Englishmen were now left in these towns. There was the deputy commissioner, of course, the chief representative of the Raj, a virtual lord over the half-a-million or so Indians who lived in the district. Then there was the superintendent of police and perhaps the chief medical officer, who were still Englishmen. All the other higher functionaries of the provincial government living in the Civil Lines, together with a couple of lawyers and doctors, were Indians. My father was one of these Indians, a magistrate dispensing justice in the district court and carrying out the tasks of civil administration in the villages.

Generally, I was content to play within the grounds of the house with my friends, mostly the servants’ children. Climbing trees to eat unripe guavas that inevitably led to stomach-aches, trying to hit pigeons with pebbles from a slingshot, fishing in the pond for nonexistent fish with a thread tied to a twig at one end and a bent pin at the other, the secret delights (and fears) of sexual games with Shanti, the sweeper’s six-year old daughter in one town and Kishen, the washerman’s precocious five-year old in another, kept me happy enough. The visits to the town’s bazaars were outings I thoroughly enjoyed but did not desperately long for. Whenever I did go to the bazaar, though, accompanying a servant on a shopping errand, I quite liked being pampered by the shopkeepers, who all knew me as the magistrate sahib’s son. I took this pampering for granted and confused it with the love I felt was my due as the only son of doting parents.

The pamperings continued in the village to which I often accompanied my father on his official tours. These tours, lasting from a week to a fortnight, were virtual expeditions. Bullock carts, and (in some districts) camels, loaded with tents, camping equipment and foodstuff, set off early in the morning while we followed more leisurely with a retinue of servants, policemen and court clerks. By the evening we would reach our destination, a village where my father would inspect the records, hear complaints and adjudicate disputes. In the falling darkness, which became magically alive with moving pinpoints of light given off by fireflies, cooking fires were lit, pleasantly scenting the air with the smoke from burning wood and buffalo-dung cakes. A stream of visitors and favour-seekers from the village would call on my father in our tent. From hundreds of years of experience as a conquered people, the villagers were well-versed in the arts of flattery, and making complimentary remarks about me was a part of their practised repertoire. By the age of six, I knew that the fawning I received from others in our retinue or from the villagers, was not always love, and that I was not the centre of everyone’s world; of course, my sister had been born by then.

While my father worked during the day in his tent, I roamed about freely in the village, intensely curious about the other children whose lives seemed so different from my own. I longed to join in their games, yet we were all aware of the gulf dividing us that was only occasionally bridged. I might have felt myself a charmed being but there was little doubt that I was outside their charmed circle. Form the beginning, then, whether in town in village, I was the insider-outsider, the child who both belonged and yet did not.

The insider-outsider situation in my culture was very much a reflection of the life history of my parents. My father had grown up in the bazaars, though in his case they were the bazaars of Lahore, the capital city of Punjab. He came from a well-to-do family of merchants and contractors and had spent his childhood and youth in a typical Indian exended family—a sprawling noisy collection of parents, a dozen brothers and sisters, and assorted uncles and aunts

on visits that in some cases could extend over a year. They all lived together in a dark three-storeyed house with little space but much warmth. My childhood impressions of life in my grandparents’ house, where I often went for extended visits, is of swirling movement and excitement contained within secure boundaries of fierce loyalty and protection with which the family surrounded each individual member, whether child, man or woman. Moving from one part of the house to another, I could, within a few mintes, be witness to loud quarrels, heart-rending sobs, tender consolations, flirtatious exchanges, uproarious laughter, and sober business conversations. The kitchen full of women—daughters of the house, female relatives and visitors presided over by my strong-willed grandmother—was active from early morning, and except for a couple of hours’ break in the afternoon closed late in the night. One ate whenever one liked and there was always a steaming hot delicacy that had just come out of the deep-bottomed frying pans. There were dozens of cousins and visiting children from the neighbourhood and we played everywhere—on the roof, from where we jumped on to the neighbouring roofs; in all the rooms of the house (there were no private spaces), as well as outside in the alley. All these spaces, inside and outside, were without boundaries, blending seamlessly into each other. Whenever I was tired, I’d find an empty bed, generally a mattress on the floor, and some woman would eventually drift over to put me to sleep. As the eldest son of the eldest son of the house, I had some privileges and could ask my favourite aunt to put aside her kitchen duties and tell me stories while I tried to fight my tiredness. The stories were usually from the Hindu epics but she also had a fund of exciting folktales about princes, princesses and magicians who turned them into birds and animals and back again into people.

My father had always been brilliant in his studies, effortlessly standing first in his class at school and in due course, he received a scholarship to study enonomics and political science at the college in Lahore. The family had placed great hopes in him. With his intellectual gifts, it was taken for granted that he would be the first one in the family to move out of the Indian world of the bazaar into the Indo-Anglian world of the Civil Lines. This move, barely a couple of miles in geographical distance but immense in cultural space, was the dream of most young men of his generation. The surest passport to this other world was by passing a competitive examination for the provincial civil service. The written examination, with an interview at its end, was very difficult; only four to five young men from all over the province were recruited for the service each year. The other routes to the Indo-Anglian world were through officer-training in the army, studies in law or medicine in England, or, through the most prestigious examination of them all, the Indian Civil Service which had been opened to Indians.

My father’s family did not have enough money to finance years of study in England. The examination for the Indian Civil Service, for which too one ideally prepared in England, was beyond my father’s cultural capabilities. To enter the service, the young man had to be at least the second if not the third generation out of the bazaar to possess the natural ease with Western manners and social sang-froid that upper-class English interviewers looked for in Indian recruits who were to be moulded into passable imitation of themselves. A short, dark man, not at all as ugly as he always thought himself to be, my father did not know how to eat with a knife and fork. He was sublimely unaware of the difference between a pink gin and a gin and tonic; indeed, having never touched alcohol, he would not have been able to distinguish whisky from rum. His acquaintance with the subtleties of cricket was slight. He neither rode, nor played tennis nor danced; he would have been tongue-tied in the presence of any young woman who was not a member of the family. What he loved was Indian-style wrestling on the banks of the river Ravi early in the morning and declaiming Sanskrit verse to admiring friends—the romantic poetry of Kalidasa in his youth and, later, when he grew older, the more cynical verses of Bharathari.

Though he had studied many of the classics of English literature and wrote a grammatically perfect though ponderous prose in the admired styles of Burke and Gibbon, he rarely spoke the language and was uncertain about the correct pronunciation of most words—a certain recipe for disaster in the ICS interviews. Later, when I, my sister or even my mother, all second-generation immigrants to the Indo-Anglian world, schooled in convents run by British missionaries of one persuasion or the other, teased him about his pronunciation of English words, his self-deprecating laughter did not quite hide his pride in the fact that he had made it possible for his children to fulfil his own ‘lack’—to speak English as the British spoke it and with a minimum of the Indian lilt in its intonation. As an adult, when I was consciously trying to get a Punjabi lilt back into my spoken English (in contrast to many friends going in the opposite direction), there was always a slight twinge of guilt for having betrayed one of my father’s cherished ideals.

My father did not have much difficulty in adapting his Indian background to the more Western lifestyle of the Civil Lines. Temperamentally incapable of being moved by religion or the beauty of Indian ritual, art or music, and with a strong belief in rationality as the ordering principle of human affairs, he was ready to identify with his British ssuperiors whom he saw as valiant fighters against the decay of an Indian society ridden with ‘magic’ and ‘superstition’. Any difficulties he may have experienced were more a matter of externals: giving up comfortable kurta-pyjamas for suits and ties, airy chappals for (given the realities of the Indian climate) smelly socks and constraining shoes. Eating porridge and toast for breakfast instead of his accustomed puri and halwa may also have given him twinges of cultural indigestion in the beginning. His readiness to adopt Western values had partly to do with his being a Punjabi and thus belonging to a people who, because of their geographical location at the gateway to India from the northwest, and historical circumstances that had made them live under a succession of alien rulers, were not as deeply anchored in traditional Hindu culture as people from most other parts of the country. The ease of his adaptation had also to do with his caste whose values and aspirations he could identify as being consonant with his own role as a civil servant of the British rule. Thus, many years later, he wrote me in a letter:

As I could follow that Khatri (our caste) was a derivation from Kshatriya, the warrior and princely class of the Vedic and classical age, I have always thought of myself belonging to a Herrenvolk when compared to other castes. I used to take pride in the fact that Khatris are, by and large, good-looking and have a fair complexion, without bothering about the fact that I possessed neither. I know I do not possess any attributes of the warrior class, yet I cling to the dogma of being a warrior type of yore, of being a ruling type with all the obligations of conduct that go with it.

My mother’s family had entered the Indo-Anglian world a generation earlier than my father’s. Her father, hailing from a village, had been a brilliant student who had managed to go to England for higher studies in medicine. After his return to Lahore, he set up a practice as a surgeon that was flourishing by the time I was born. My mother, as also her sisters and brothers, was educated at English-speaking schools, and their house on Lawrence Road in Lahore was a grander version of the houses in the district towns where I spent my childhood. My memories of my maternal grandparents’ house are quite different from those of my father’s family. There was, of course, much more space in this house as also a greater order; there was more privacy for the individual family member, but also many more prohibitions. There was little of the indulgence and easygoing acceptance of children and their ways that was a characteristic of my father’s family—my mother’s father being a believer in strict discipline for the child and other such Western notions.

For me, the best part of the visits to my mother’s family was provided by the circumstance that my grandmother’s family owned a cinema in Lahore. With the help of a friendly usher who also doubled as an odd-job man around the house, I spent many delightful afternoons at the cinema, seeing a

movie 15 to 20 times and thus beginning a love affair with the world of Hindi films that has continued to this day. Like everything else in India, from plants to men, the movies too were divided into a hierarchy. In the caste order of Hindi films, the Brahmin ‘mythological’ about the legends of gods and goddesses were at the top, followed by the Kshatriya ‘historicals’, while the Sudra ‘stunt’ films were at the bottom. My taste in movies, however, was catholic, consisting of indiscriminate adoration. As I sat there in the darkened hall, in the company of students giving their teachers a temporary breather and domestic servants prolonging their shopping errands, I felt no longer a small child from a provincial town but very much a man of the world. Watching flickering images on the screen portraying a love scene and trying to understand the loud remarks and double-entendres from the audience that were met by bursts of appreciative laughter in which I too joined, I felt tantalisingly closer to unravelling that secret of adulthood which every child yearns to understand. Now, in their familiar, unchanging plots and treatment, Hindu films keep the road to childhood open.

The cinema, the house on Lawrence Road and in the bazaar, were all lost during the Partition of the country in 1947. Caught up in the tidal wave of migration from Pakistan to India, the families of my parents were irrevocably scattered all over the country as individual members tried to fend for themselves and build new lives. My mother’s father, for instance, went to the far eastern corner of the country—to Assam—to head a newly created medical college. My other grandfather, together with a couple of still unmarried aunts and an uncle, settled in Amritsar at the opposite end of the new country. The long and frequent visits to my parents’ families, the closeness with uncles, aunts and cousins, became a thing of the past. From regular immersions into the river of extended family life, with its rituals and festivals, games and feasts, and rapidly shifting alliances of love and hate, my life became a narrow stream bounded by the world of Christian missionary schools on one side and of my parents and my sister on the other. For me the Partition of the country also effectively marked the end of my childhood.

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

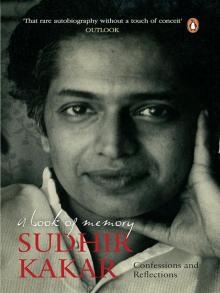

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory