- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

The Indians

The Indians Read online

Sudhir Kakar & Katharina Kakar

THE INDIANS

Portrait of a People

Contents

About the Authors

Introduction

The Hierarchical Man

The Inner Experience Of Caste

Indian Women: Traditional and Modern

Sexuality

Health And Healing; Dying and Death

Religious and Spiritual Life

Conflict: Hindus and Muslims

The Indian Mind

Notes and References

Follow Penguin

Copyright

About the Authors

Sudhir Kakar is an internationally renowned psychoanalyst and writer. He has been a visiting professor at the universities of Chicago, Harvard, McGill, Melbourne, Hawaii and Vienna and a Fellow at the Institutes of Advanced Study, Princeton and Berlin. Currently, he is Adjunct Professor of Leadership at INSEAD in Fontainbleau, France. His many honours include the Bhabha, Nehru and National Fellowships in India, the Kardiner Award of Columbia University, the Boyer Prize of the American Anthropological Association, and Germany’s Goethe Medal. The leading French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur listed him as one of twenty-five major thinkers of the world.

Sudhir Kakar’s books have been translated into twenty languages around the world. His non-fiction books include The Inner World: A Psychoanalytical Study of Childhood and Society in India; Intimate Relations: Exploring Indian Sexuality; The Analyst and the Mystic: Psychoanalytic Reflections on Religion and Mysticism and The Colours of Violence. His three published novels are The Ascetic of Desire, Ecstasy and Mira and the Mahatma. He has also translated (with Wendy Doniger) Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra. He lives in Goa.

*

Katharina Kakar studied Comparative Religions, Indian Art and Anthropology at the Free University of Berlin. She has taught at the Free University and the College of Protestant Theology, Berlin and was a Fellow at the Centre of the Study of World Religions at Harvard University. She is the author of the books Hindu-Frauen zwischen Tradition und Moderne (Hindu Women between Tradition and Modernity) and Der Gottmensch aus Puttaparthi: Eine Analyse der Sathya-Sai-Baba-Bewegung und ihrer Westlichen Anhänger (The Godman of Puttaparthi: An Analysis of the Sathya-Sai-Baba-Movement and its Western Devotees).

PRAISE FOR THE INDIANS

‘This is a book which should be read by all Indian executives’—Mark Tully, Financial Express

‘ This stimulating book is a magnificent attempt to understand Indian life in all its fullness . . . deepens our understanding of not just our lives but our minds as well’—The Statesman

‘Mr and Mrs Kakar display an encyclopedic and deep understanding of the Indian social reality, their “way of looking at things” is surpassed by none’—Far Eastern Economic Review

‘This incisive book . . . succeeds in great measure in understanding and explaining the Indian character’—Deccan Herald

‘Both intellectually rigorous and sensitive, Sudhir Kakar is a reliable guide to how Indians today experience their identity, their sexuality, their conflict between tradition and modernity’—Le Monde, France

‘A very readable and richly nuanced book which seeks to uncover the common identity of ‘The Indians’ in their historical continuity, homogeneity and civilizational uniqueness’—Neue Zuricher Zeitung, Switzerland

‘The fascinating portrait of the society and culture of a country that will play an ever more important role in world politics in the future’—Die Zeit, Germany

Introduction

Our book is about Indian identity. It is about ‘Indian-ness’, the cultural part of the mind that informs the activities and concerns of the daily life of a vast number of Indians as it guides them through the journey of life. The attitude towards superiors and subordinates, the choice of food conducive to health and vitality, the web of duties and obligations in family life are all as much influenced by the cultural part of the mind as are ideas on the proper relationship between the sexes, or on the ideal relationship with god. Of course, in an individual Indian the civilizational heritage may be modified and overlaid by the specific cultures of his family, caste, class or ethnic group. Yet an underlying sense of Indian identity continues to persist, even into the third or fourth generation in the Indian diasporas around the world—and not only when they gather for a Diwali celebration or to watch a Bollywood movie.

Identity is not a role, or a succession of roles, with which it is often confused. It is not a garment that can be put on or taken off according to the weather outside; it is not ‘fluid’, but marked by a sense of continuity and sameness irrespective of where the person finds himself during the course of his life. A man’s identity—of which the culture that he has grown up in is a vital part—is what makes him recognize himself and be recognized by the people who constitute his world. It is not something he has chosen, but something that has seized him. It can hurt, be cursed or bemoaned but cannot be discarded, though it can always be concealed from others or, more tragic, from one’s own self.

The cultural part of our personal identity, modern neuroscience tell us, is wired into our brains. The culture in which an infant grows up constitutes the software of the brain, much of which is already in place by the end of childhood. Not that the brain, a social and cultural organ as much as a biological one, does not keep changing with interactions with the environment in later life. Like the proverbial river one never steps into twice, one also never uses the same brain twice. Even if our genetic endowment were to determine fifty per cent of our psyche and early childhood experiences another thirty per cent, there is still a remaining twenty per cent that changes through the rest of our lives. Yet, as the neurologist and philosopher Gerhard Roth observes, ‘Irrespective of its genetic endowment, a human baby growing up in Africa, Europe or Japan will become an African, a European or a Japanese. And once someone has grown up in a particular culture and, let us say, is twenty years old, he will never acquire a full understanding of other cultures since the brain has passed through the narrow bottleneck of “culturalization”.’1 In other words, the possibilities of ‘fluid’ and changing identities in adulthood are rather limited and, moreover, rarely touch the deeper layers of the psyche. So, in a sense, we are Spanish or Korean—or Indian—much before we make the choice or identify this as an essential part of our identity.

We are well aware that at first glance the notion of a singular Indian-ness may seem far-fetched. How can anyone generalize about a country of a billion people—Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Jains—speaking fourteen major languages and with pronounced regional differences? How can one postulate anything in common between a people divided not only by social class but also by India’s signature system of caste, and with an ethnic diversity characteristic more of past empires than of modern nation states? Yet from ancient times, European, Chinese and Arab travellers have identified common features among India’s peoples. They have borne witness to an underlying unity in apparent diversity, a unity often ignored or unseen in recent times because our modern eyes are more attuned to spotting divergence than resemblance. Thus in 300 BC, Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to Chandragupta Maurya’s court, remarked on what one would today call the Indian preoccupation with spirituality:

Death is with them a frequent subject of discourse. They regard this life as, so to speak, the time when the child within the womb becomes mature, and death as a birth into a real and happy life for the votaries of philosophy. On this account they undergo much discipline as a preparation for death. They consider nothing that befalls men as either good or bad, to suppose otherwise being a dream-like illusion, else how could some be affected with sorrow and others with pleasure by the very same thing

s, and how could the same things affect the same individuals at different times with these opposite emotions?2

In more recent times, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, wrote in his The Discovery of India:

The unity of India was no longer merely an intellectual conception for me; it was an emotional experience which overpowered me... It was absurd, of course, to think of India or any country as a kind of anthropomorphic entity. I did not do so... Yet I think with a long cultural background and a common outlook on life develops a spirit that is peculiar to it and that is impressed on all its children, however much they may differ among themselves.3

This ‘spirit of India’ is not something ethereal, inhabiting the rarefied atmosphere of religion, aesthetics and philosophy, but is captured, for instance, in animal fables from the Panchatantra or tales from the Mahabharata and Ramayana that adults tell children all over the country. It shines through Indian musical forms but is also found in mundane matters of personal hygiene such as the cleaning of the rectal orifice with water and the fingers of the left hand, or in such humble objects as the tongue scraper, a curved strip of copper (or silver in the case of the wealthy) used to remove the white film that coats the tongue.

Indian-ness, then, is about similarities produced by an overarching Indic, pre-eminently Hindu civilization that has contributed the lion’s share to what we would call the ‘cultural gene pool’ of India’s peoples. In other words, Hindu culture patterns—which are the focus of this book—have played a very major role in the construction of Indian-ness, although we would hesitate to go as far as the acerbic critic of Hindu ethos, the writer Nirad C. Chaudhuri, who maintained that the history of India for the last thousand years has been shaped by the Hindu character and that he felt ‘equally certain that it will remain so and shape the form of everything that is being undertaken for and in the country.’4 Here we can mention only some of the key building blocks of Indian-ness, which we will elaborate upon in this book: an ideology of family and other crucial relationships that derives from the institution of the joint family; a view of social relations profoundly influenced by the institution of caste; an image of the human body and bodily processes that is based on the medical system of Ayurveda; and a cultural imagination teeming with shared myths and legends, especially from the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, that underscore a ‘romantic’ vision of human life and a relativist, context-dependent way of thinking.

We do not mean to imply that Indian identity is a fixed constant, unchanging through the march of history. Indic civilization has remained in constant ferment through the processes of assimilation, transformation, re-assertion and recreation that happened in the wake of its encounters with other civilizations and cultural forces, such as those that came with the advent of Islam in medieval times and European colonialism in the more recent past. Virtually no part of Indic civilization has remained unaffected by these encounters, be it classical music, architecture, ‘traditional’ Indian cuisine or Bollywood musical scores. Indic civilization has not so much absorbed as translated foreign cultural forces into its own idiom, unmindful or even oddly proud of all that is lost in translation. The contemporary buffeting of this civilization by a West-centric globalization is only the latest in a long line of invigorating cultural encounters that can be called ‘clashes’ only from the shortest of time frames and narrowest of perspectives. Indic civilization, as separate from though related to Hinduism as a religion, is thus the common patrimony of all Indians, irrespective of their professed faith.

Indians, then, share a family resemblance in the sense that there is a distinctive Indian stamp on certain universal experiences which we shall discuss in this book: growing up male or female, sex and marriage, behaviour at work, status and discrimination, the body in illness and health, religious life and, finally, ethnic conflict. In a contentious Indian polity, where various groups clamour for recognition of their differences, the awareness of a common Indian-ness, the sense of ‘unity within diversity’, is often absent. Like the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges’ remark on the absence of camels in the Quran because they were not exotic enough to the Arabs to merit attention, the camel of Indian-ness is invisible to or taken for granted by most Indians. Their ‘family’ resemblance begins to stand out in sharp relief only when it is compared to the profiles of peoples of other major civilizations or cultural clusters. A man who is an ‘Amritsari’ in Punjab, for instance, is a Punjabi in the rest of India but an Indian in Europe; in the latter case, the ‘outer circle’ of his identity—his Indian-ness—becomes central to his self-definition and his recognition by others.5 This is why in spite of persistent academic disapproval, people (including academics in their unguarded moments) continue to speak of ‘the Indians’—as they do of ‘the Chinese’, ‘the Europeans’ or ‘the Americans’—as a necessary and legitimate short cut to a more complex reality.

Our aim in this book is to present a composite portrait in which Indians will recognize themselves and be recognized by others. This recognition cannot have a uniform quality even while we seek to identify the commonalities that underlie what the anthropologist Robin Fox calls the ‘dazzle’ of surface differences. We suspect that Hindus belonging to the upper and middle castes will see a picture in which they will find many features that are intimately familiar. Others at the margins of Hindu society (such as the dalits and tribals, or the Christians and Muslims) will spot only fleeting resemblances. Even in the case of Hindus, who constitute over eighty per cent of India’s population, the portrait is not a photograph. But neither is it a cubist representation à la Picasso where the subject is barely recognizable. Our effort is more akin to the psychological studies of such expressionist painters as Max Beckman and Oskar Kokoschka or, nearer to our times, the portraits of Lucien Freud that use realism to explore psychological depth.

We are also aware that what we are attempting here is an unfashionable ‘big picture’, a ‘grand narrative’ that may be regarded with reflexive hostility by many who profess the postmodernist credo. Yes, there is a speculative quality in this exercise of settling on certain patterns of Indian-ness as central. Yet without the big picture—whatever its flaws of inexactness—the smaller, local pictures, however accurate, will be myopic, a mystifying jumble of trees without the pattern of the forest.

The Hierarchical Man

In an article titled ‘Where rank alone matters’, the well-known Indian journalist Sunanda K. Datta-Ray writes that the gratification of 300 million middle-class consumers, the ‘new brahmins’, does not lie in their being consumers in a global marketplace but in being ‘somebody’ in a profoundly hierarchical society.1 Retired judges, ex-ambassadors and other sundry officials of the Indian state who are no longer in service are never caught without calling cards prominently displaying who they once were. India is not a country for the anonymous, he concludes. You must be somebody to survive with dignity, since rank is the only substitute for money. He could have added that India also provides by far the largest number of aspirants for the Guinness Book of Records. The Indian ingenuity in finding ever new fields for setting records (and we are not talking about the well-known ones for the longest fingernails or the largest moustache) is remarkable, amusing, and oddly touching. Commercially astute British and American publishers of biographical dictionaries and compendia of ‘Who’s Who’—a lucrative branch of vanity publishing—have discovered that India provides the biggest market for people wanting to be included in such publications which are then prominently displayed in the living room of their homes.

The need to be noticed, to stand out from an anonymous mass, is, of course, not uniquely Indian but a part of the narcissistic heritage of all human beings. What makes this phenomenon particularly ubiquitous—and poignant—in India is that a person’s self-worth is almost exclusively determined by the rank he (alone or as part of a family) occupies in the profoundly hierarchical nature of Indian society. If the perception of another person has first to do with gender (�

�Is this individual male or female?’), followed by age (‘Is he/she young or old?’) and by other such markers of identity, then in India the determination of relative rank (‘Is this person superior or inferior to me?’) remains very near the top of subconscious questions evoked in an interpersonal encounter. Indians are perhaps the world’s most undemocratic people, living in the world’s largest and most plural democracy.

The deeply internalized hierarchical principle, the lens through which men and women in India view their social world, has its origins in the earliest years of a child’s life in the family. Indeed, a grasp of the psychological dynamics of family life is vital not only for understanding Indian behaviour towards authority but also in a wide variety of other social situations.

THE WEB OF FAMILY LIFE

The Indian family: large and noisy, with parents and children, uncles, aunts and sometimes cousins, presided over by benevolent grandparents, all of them living together under a single roof. There are intrigues and secret liaisons, fierce loving and jealous rages. Its members often squabble among themselves but remain, in most cases, intensely loyal to each other and always present a united front to the outside world. The Indian family—animated with such a powerful sense of life that a separation from it leaves one with a perpetual sense of exile.

This is the ‘joint’ family of Bollywood movies which, social scientists tell us, has never been a universal norm. It is also untrue that the large joint family is found more often in villages than in cities; studies tell us that it is more common in urban areas, as also among the upper landholding castes, than in the lower castes of rural India. Economic reasons, especially the high cost of urban living space, are certainly a reason why the joint family survives. Contemporary nostalgia at the supposed withering away of the Indian family with the increasing pace of modernization could well be misplaced; the prevalence of joint families may be increasing rather than declining.2 It is important to note that irrespective of demographic changes and the desire of many modern middle-class couples to escape the tensions of a large family and live on their own, the joint family remains the most desirable form of family organization and has a psychic reality independent of its actual occurrence.3

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

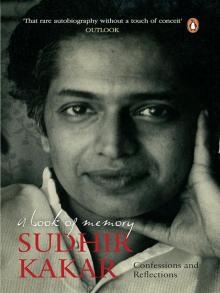

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory