- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

The Crimson Throne Page 2

The Crimson Throne Read online

Page 2

I too had a narrow escape once. One of these fidalgos, with his ridiculous sense of honour, felt he needed to avenge himself under the false impression that I was putting the horns on him. I shall tell that story in its proper place. Here, I only wish to say that I did not leave Goa because of that incident. That is a despicable lie, a malicious rumour spread by my enemies at the Mogul court. I shall not be surprised at that lying Frenchman M. Bernier’s involvement in its dissemination. It was simply time for me to leave Goa to seek my fortune further north, in the heart of the Mogul empire.

The anarchy prevailing in Goa was, in fact, worse than what one encounters in the most violent quarters of any European port. I learned from my mestica friends that till a few months before my arrival bands of Kaffirs freely roamed the city at night, intent on robbery and murder. At one time, when Goa was prospering, rich merchants would employ fifty or even a hundred African slaves, but as times changed they let the slaves go. Feared and despised, and with no means of earning an honest living, the Kaffirs took to waylaying and killing anyone foolish enough to be out at night and plundering lightly guarded houses. Finally, they became bold enough to attack Portuguese soldiers. Each day a dozen or more guards would be found lying dead in the streets, with the result that the Viceroy ordered a curfew on the Kaffirs from eight at night till six in the morning. Night patrols were increased and the soldiers instructed to kill any Kaffirs they encountered wandering the streets after the curfew hour. On the very first morning after the Viceroy’s order, two hundred corpses of the poor wretches were found in various parts of the city. This continued for a week till the Kaffirs were intimidated. Not that the Portuguese guards were much better than the Kaffirs. Robberies and murders may have decreased, but assaults and rapes became more common.

Though threatened, the Kaffirs did not disappear from the streets but simply broke into smaller bands. They now did their robbing in the afternoon and at smoky dusk before the night curfew began. Hindu shopkeepers in the outskirts of the city, who could not afford to employ guards, faced the worst of it. They kept the doors of their shops locked from inside even during the day and made large holes in the door through which they received money and handed out articles of daily use. But even this precaution was not enough. Apparently, six months before my arrival, two Kaffirs approached a shopkeeper, pretending to buy twenty red peppers. When the shopkeeper extended his hand for the money, one of the Kaffirs seized it and held it down while the other pricked it continuously with a knife, threatening to cut off the hand if the shopkeeper did not give them all of his money. The petrified shopkeeper called out to his wife to gather all the money in the house and give it to them. But the Kaffirs still cut off two of the man’s fingers before releasing his hand. He had given them two chillies less, they said. Following this incident, Hindu shopkeepers no longer extended their hands through the hole. Instead, they used long wooden spoons to supply goods and accept money in exchange.

You may ask why I spent a year in Goa if my prospects of making a quick fortune through voyages to China and Japan had disappeared even before I arrived. In reply, I can only point to my guiding star. France. I venture to say I have done so with more boldness and even greater success than those travellers who have been more fortunate in being born with a title or to wealth.

My hope is that this account of my travels will meet the expectations of learned and discerning personages. If they find these memoirs written in a style devoid of elegance then I hope they will not consider it extraordinary that during the long absence of twelve years from France my language may have become semi-barbarous. If I have interposed in certain places stories which might relieve the mind after descriptions of land, people and travel, I have done so in imitation of the orientals who establish caravanserais at intervals in their deserts to provide relief to travellers. My purpose throughout this account, however, is instruction and elevation rather than amusement and diversion. I acknowledge that because of my interest in politics and the social life of a land, I have neglected the reader who is connected with commerce and desires to know what India produces, through art and nature, for the enjoyment of European nations.

I do not hesitate to admit that given my sober, even earnest, disposition I am not the ideal person to introduce a foreign land and its people. The Indians maintain that the mind of a man cannot always be occupied with serious affairs, and that he remains forever a child in this respect. To develop what is good in him, almost as much care must be taken to amuse him as cause him to study. The Indians—and I speak not of the believers in the religion of Mohammed but of the Gentile idolaters—for all their claims to antiquity, are a surprisingly young, even childishly naïve race in their approach to serious affairs, of state or, indeed, of life. Yet there is merit to their argument, since some of our more pessimistic European philosophers, despairing of the human capacity for seriousness, have grudgingly conceded that the more abstract the matter you wish to teach, the more you will have to seduce the senses to it.

Although I agree with Plutarch that trifling incidents—whose main source in the Indies is bazaar gossip—ought not to be concealed as they often enable us to form more accurate opinions of the genius of a people and their monarchs than events of signal importance, I prefer to be a sober observer of people and events in order that my record of them will one day be deemed accurate history. Thus, unlike most Indians, who tend towards frivolity—and a certain Italian quack who dispenses potions to the credulous at the imperial court and dignifies all manner of gossip—I view people’s appearance or apparel, their manners and customs, learning and pursuits, beliefs and habits, mores and morals as more instructive than diverting and thus more attuned to the taste of my intended audience that is as educated as it is discriminating. This does not mean that I will excise my account of every trifling incident; I hold only that any such incident included in a serious history be truthful and not have its birth in the fancy of the populace, or that of the writer.

Before beginning my account, I shall briefly introduce myself, not in the manner of a braggart hoping for applause for achievements that loom large in his own mind alone, but to acquaint the reader with my origins and possible prejudices so that he may better judge the accuracy of my opinions and, if he finds it advisable, discount some of my conclusions.

I was born on the twenty-fifth day of September, 1620, at Joue, near Gonnard, in Anjou. My parents were honest and devout; my father was a yeoman who leased and cultivated land that belonged to the Canonery of St Maurice at Angers in the Barony of Etiau. My aquiline features and high-domed forehead bear no trace of my peasant ancestry, I have often been told, an intended compliment that gratifies me less at present than it did when I was younger.

The only vivid memory I have of my early years is of looking up at my father’s powerful shoulders bunched between the shafts of a horse-plough, his narrowed eyes fixed on the ground, his clicking tongue goading the horses forward, while I stumbled around the farm in his broad shadow. I became an orphan at the age of five when my parents were taken by a mysterious fever, and was cared for by my uncle, the curé de Chanzaux, till the age of fifteen, when I moved to Paris to study at the Collège de Clermont.

Since my intention in these memoirs is to be a witness, no more than ears and eyes to remarkable happenings, I shall keep an account of how a peasant’s son came to travel in the lands of Eastern potentates to a minimum. Suffice to say that when I was entering my youth, a series of fortunate events brought me to the attention of M. Pierre Gassendi, the famous philosopher. M. Gassendi adopted me as his protégé and took personal charge of my education. Indeed, that great man whom many consider as the heir of Montaigne, did me the signal honour of employing me as his secretary before he died. He also graciously invited me to move into his own house, where I was to occupy a spacious, well-lit room with a large bay window with a pleasing prospect of the garden. His beneficence allowed me to give up my ill-furnished room in a boarding house on Rue Pierre-a-Poisson where each morn

ing I had to make my way past shouting fishmongers and their jostling customers, sometimes being pushed against long tables heaped with river fish and at other times avoiding rats scurrying through the stinking fish offal.

The character of M. Gassendi’s intellect, both inventive and critical, the liveliness of his imagination and the retentiveness of his memory, have been earlier commented on by his many admirers and colleagues, who are infinitely more erudite and better judges of his contributions to the world of knowledge than I can ever hope to be. What these personages have not sufficiently stressed is his curiosity about distant lands, a curiosity he passed on to me as his inheritance. My travels were, thus, not undertaken as a result of the feelings of unsettledness that routinely beset young men, but were driven by a thirst to know and compare rather than merely see and enjoy the towns and countryside, the inhabitants and productions, of a foreign land.

It was on M. Gassendi’s advice that I studied medicine before setting out on my travels. While preparing me for the examination in physiology at the University of Montpellier, he often reiterated his conviction that of all professions a doctor was the most reliable guide to the understanding of foreign peoples and their mores. ‘You will know more about other people by helping them than by merely observing them. If you would gain knowledge of a man, it is better to do things for him and with him than to stand apart or, worse, do things to him,’ he said. M. Gassendi’s wisdom was not a whit less than the generosity of his spirit.

After graduating as licentiate in medicine in 1652, I spent most of my nights as a young resident surgeon among the Gothic portals of Hospital Dieu, its long passages crammed with sick-beds, reading Father Monserrate’s account of his years at the court of Akbar, the grandfather of the present emperor Shah Jahan; all three volumes of Father Pierre du Jarric’s Histoire de Choses plus Memorables Advenues; and two volumes of the Italian Pietro della Valle’s travels in India.

‘Study these books well, Bernier,’ M. Gassendi would say, ‘and you may reasonably hope to arrive in India a stranger, yet one who will not be shocked by that weird and wonderful country’s onslaught on a visitor’s senses and reason.’

Like most accounts of travel, these volumes were often tedious reading for me. I freely concede that my interests are not all-encompassing. I am often as one blind to the physical features of a land: to its flora and fauna, to the habitat and habitations of its people. My curiosity, influenced no doubt by the example of my esteemed teacher, prefers to dwell on human beings and, if afforded an opportunity, dart into their characters.

Once in India, I had hoped to go to the Mogul court in Delhi as soon as possible to offer my services as a physician. European physicians, I had heard, were considered superior to native Mohammedan hakims and the idolater vaids in most branches of medicine, particularly in the treatment of war wounds. While a resident at Hospital Dieu in France I had worked under the guidance of M. Pissier, himself a pupil of the renowned surgeon Ambrois Parre, who had revolutionized the care of amputated stumps on the battlefield. (War is indeed the mother of all invention!) I was well versed in the care of such injuries and in employing the Parre method of tying off arteries to control bleeding, followed by the application of an ointment prepared from a cold mix of egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine to the wound, thus eliminating the old method of cauterizing the bleeding part with a red-hot iron or boiling oil. I was aware that native doctors were unfamiliar with such medical advancements and was thus sanguine about my prospects of finding honourable employment at the Mogul court. I could have never foreseen at the time that at the end of my eleven-year stay in the country, I would be holding the position of a personal physician to the emperor himself!

It was well into the spring of 1657 when I finally boarded a vessel which brought me to Surat, a bustling port on the west coast of India on the bank of a river nine leagues inland from the sea. My funds were nowhere near exhaustion, but possessing the prudence of age while still a youth I did not wish to tarry in Surat for even a day more than necessary. I had made up my mind to proceed immediately to the imperial court in Delhi. Providence, however, decreed that I postpone my departure for almost three weeks while I recovered from a mysterious tropical ailment. This unforeseen delay was a godsend as it enabled me to become more familiar with the country, by now absorbing it through the senses rather than through books.

If my memories of Surat are blurred then it is not only due to the fastidious nature of my cognition but also, and more prosaically, because I was indisposed with a low fever and loss of appetite for most of these days. I was fortunate to find shelter at the residence of M. Briffault, a fine and noble gentleman who liked to dress in loose Indian robes, wore a monocle in the English fashion and who had been deputed by our monarch to explore the possibility of establishing a French factory in Surat. I therefore spent the most vulnerable days of my travels—when I was physically ill in a country which can be forbidding to a European encountering it for the first time—in an ambience which, if not totally French, was also not quite Indian, thus providing me with a transitional haven when I needed one the most.

My first impressions of India were mainly gathered from the windows of M. Briffault’s carriage, which my host, who sometimes accompanied me on these outings, graciously put at my disposal after the bout of fever had passed and I had begun to regain my strength.

What struck me the most was the sheer number and variety of people on the streets, more than I would ever see in Paris or Marseilles. Their complexions ranged from Persian pale to Negro teak and they were garbed in diverse dress and headgear. This diversity, however, was not raw confusion but presented a pattern to the initiated eye. ‘You will notice, M. Bernier,’ M. Briffault had said, ‘that the turbans the Mohammedans wear are white and round while those of the idolaters are coloured, straight, high and pointed. And if you’re wondering at the crowds in the streets and in the bazaars, you will need to return here in the monsoon when the country is lashed by heavy rains. During those months ships avoid the open seas and seek shelter here. They are loaded with merchandise as they wait and the town is so full of people that it is almost impossible to find lodging.’

Although the idolater men are generally short and unprepossessing, their darkly bronzed women with bold black eyes and glossy black hair, tied in a bun behind the neck or twisted in the form of a pyramid above the head, hold an undeniable attraction which, some might say, is less aesthetic than basely visceral. I am speaking, of course, only of the idolater women of lower classes who walk on the street with their faces uncovered. The upper-class women, both idolater and Mohammedan, are carried in decorated palanquins closed on all sides, with a thick piece of silk curtaining the two tiny windows and the entrance. Even the poorer Mohammedan women on the country, like the women of Turkey and Persia, never venture out on the street unveiled. They cover themselves with a white shroud that falls down to their ankles and has a narrow slit covered with a fine net in front of the eyes. The dress of the idolater women is generally a simple cotton cloth, white or coloured, which is bound five or six times like a petticoat from the waist downwards, with cunning folds in front that makes it look as if they are wearing three or four petticoats, one above the other. Well-born women throw one end of this cloth across their breasts while those belonging to the lower tribes are indifferent about the matter. Indeed, the Banjara women, a nomad folk who transport goods from one part of the country to another and are thus often encountered in groups on the streets of Surat, tattoo their skin from the waist upwards with flowers, which are then painted in different colours with the juice of roots. I was always quick to avert my gaze from Banjara girls although I can well imagine that the sight of their firm breasts and sooty, prominent nipples, colourfully decorated in this manner, can be occasion for concupiscent excitement in men with a lewd disposition.

I found M. Briffault a congenial companion who shared my liberal persuasion, which proved often to be at odds with that of the other Europeans with whom I made acq

uaintance. These were no more than twenty in number and were all attached to the English and Dutch factories in Surat. The worst of these was a Mr Charles Morley who ran the English factory and who, M. Briffault informed me, was overly fond of catamites in which the Indies abounds. A stout man, whose ill-fitting wig accentuated his balding pate rather than hiding it, Mr Morley had lived in India for eleven years and regarded himself as an authority on the land and its peoples. For some inexplicable reason, this man took a liking to me in a rare contradiction of M. Gassendi’s adage ‘If you do not like a person, Bernier, you can be certain that the person also dislikes you’, and sought every opportunity to turn up at M. Briffault’s house in the evening to enlighten me on the imperfections of this country and the utter stupidity of the idolaters who constitute by far the largest part of its population.

‘Do you know, M. Bernier, that they run hospices for cows, horses, dogs, cats and even insects and flies? Is that not a testimony to the boundless foolishness of these people? In one of these hospices, I saw a white-bearded venerable old man diligently feeding little orphaned mice milk with a bird’s feather because they were so small that they could eat nothing else!’

‘M. Bernier, do not believe all that Morley says about the idolaters. His facts may be right but his judgements are seriously flawed,’ M. Briffault said after the Englishman had left. ‘The idolaters of Surat are indeed an odd people who do not eat meat of any kind, preferring to subsist on tasteless vegetables and lentil gruel. They are, however, no more eccentric than the rest of their race whose religious beliefs and living habits would appear ludicrous to any right-thinking Christian. Personally, I find the idolaters of India a race that is more unfortunate than depraved. Belonging to an earlier stage of mental if not material development—for they are capable of manufacturing the most exquisite goods—the idolaters can hold up to us a mirror of a past which we left behind when our Christian faith delivered us from the superstition and idolatry that still holds the people of the Indies in an iron thrall.

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

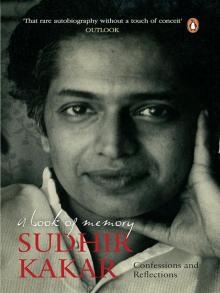

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory