- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

Indian Love Stories Page 4

Indian Love Stories Read online

Page 4

‘Yes!’

‘There’s really nothing I could do. The train was quite late – otherwise I would have been here a couple of hours ago.’

Anadi Ray started undoing a bedding with much enthusiasm. Madhuri objected, ‘Please don’t bother I’m perfectly all right.’

‘You’ll feel better if you lie down and take a rest.’

‘Don’t bother please, for such a short time.’

But Anadi Ray was not to be dissuaded. He opened a suitcase, took out a woollen wrapper, folded it once and put it carefully round Madhuri’s shoulder.

All the while Satadal sat still on a chair and took in the scene, which struck him as funny as well as cruel and rather unbecoming. It was not possible, however, to remain still any more. He got up, went up to the door and looked out. Then he came back and needlessly moved various pieces of his luggage. He fidgetted like one imprisoned in a cell in punishment. As though he was looking for some way to escape from this confinement and get some peace elsewhere!

What was happening was intolerable. The woollen wrapper appeared to have given Madhuri some comfort, removing all her tiredness from the journey. And that gentleman, named Anadi Ray, looked so proud and smug sitting there beaming with happiness. And Madhuri was like a bride in a fairy-tale, who after a brief pretence, garlanded her predestined prince, who would take her away in his chariot. And like a totally defeated contestant, Satadal looked on in utter humiliation and hopelessness. This was hard to bear.

But why didn’t he flee the scene? What compelled him to suffer the humiliation of watching what was happening?

He could not go away because of one temptation – the temptation to know Madhuri’s answer to the question he had put to her.

But why this temptation?

If Madhuri would only say she hadn’t been able to forget him – that would give him the delight of a triumph and he would go away content.

But what kind of delight would that be? Satadal didn’t know. He kept on staring at Madhuri, the picture of peace and quiet.

He suddenly came out of this state, for it dawned on him he might never get any opportunity to know her answer. Madhuri was putting on her overcoat. She appeared anxious to flee.

Anadi Ray also looked at his watch. Probably it was time for departure. The porter came; yes, the train to Patna was about to arrive.

Madhuri Ray, wife of Anadi Ray, stood very near her husband as the porter lifted their luggage on to his head. She was about to leave setting fire, Satadal imagined, to a combustible house.

That world of seven long years! Could one forget that by a mere act of one’s will! Could one tear that away from one’s life, throw that away. Madhuri was not going to answer these questions – there was now no opportunity for her to do so.

It would have been better if Madhuri could go away happily, walking beside her husband, not caring to look back. But she couldn’t quite do that. The porters went out and Anadi Ray also took a few steps out of the room, but Madhuri, as she reached the door, stopped and, on the verge of her final departure, looked back as if to glance at the burning house she was leaving behind for which she felt some unearthly compassion.

Then she looked at Satadal and said, ‘I am going.’

Satadal tried, unsuccessfully, to smile, while he was choked by an uprush of yearning and a sense of deprivation. There was little time to say anything. He would be comforted if she had an answer to his question.

‘Yes, of course, you must be going – but you didn’t answer my question, Madhuri.’

Madhuri stopped smiling, and asked, as if she was surprised, ‘What question?’

She didn’t reply. Maybe she had forgotten. But if she remembered the history of seven years, how could she forget what was asked seven minutes ago! Surely the world had not gone topsy-turvy within this period to make her forget that! Satadal was puzzled.

Madhuri repeated, ‘I’m going. It’s getting late.’

This was a rude shock which shattered Satadal’s temptation and curiosity. He remembered Madhuri had a definite destination; she must get there without delay. He had no right whatever to get in her way. He made her delay for seven years but not now – he had no right anymore.

He looked crushed, ‘I know you won’t answer.’

She was calm, ‘No answer is called for.’

‘Why?’

‘Because that’s a very unfair question.’

‘I see,’ he said and stood up from the chair. But some foolish lingering temptation would not let him accept the situation. He persisted in looking the other way and what he blurted out was quite rude. ‘You’ll of course go away, but it was quite unnecessary to act out this funny scene.’

These were bitter words, and they made her stiff. She thought for a while and then smiled as before. Probably she resolved not to fan the flaming house behind her, rather she decided to try to put out the flames and make him laugh a little if possible.

She glanced at her wrist-watch and said, ‘Please come to Rajgir once, won’t you, with Sudha and spend a few days with us.’

‘But why?’ Satadal wondered.

‘Why not, you can come if you just wish to.’

‘And then?’

‘I’ll then see you two off at the railway station when you leave.’

‘What for?’

‘Because you would then get an opportunity to enact a funny scene.’

‘What would you gain by that?’

Madhuri answered with a smile, ‘No gain, but perhaps I’ll also get angry and say some worthless words as you did.’

Satadal looked on for a second or two and then said, ‘Now I see,’ then he laughed out.

He spoke the last few words quite loud and continued to laugh. As if the temptation and desire contained in his worthless words now saw themselves in their true light and that realization turned them into laughter. Satadal saw it all at last.

He looked at his wrist-watch and realized, without looking at the door, that Madhuri had left.

The combustible house did not catch fire; it reverbated with his loud laughter. Rajpur junction woke up. The train to Calcutta also arrived and there was some bustle on the platform which was on the other side; Satadal was walking briskly to catch the train, accompanied by a porter with his luggage on his head.

In the early hours of that cold night those two trains went in opposite directions. Rajpur Junction would be quiet again. And what a drama was enacted in the waiting room involving two passengers. There would not be any trace or record of all that had happened.

For a while there were still some indications. Though looking at them one would not have thought so – a tray and two cups on it.

Translated from the Bengali by

DIPEN MITRA

STAINS

Manjula Padmanabhan

t was a tiny mark, barely visible. Yet Mrs. Kumar was holding the sheet between her thumb and forefinger as if she feared that merely to be in the presence of such a sheet might mean eternal damnation. Merely to know of the existence of such sheets.

She said, ‘Blood’.

Sarah said, ‘Yes,’ while wondering whether she should apologize. ‘I’m sorry,’ she heard her voice say, ‘I – I’m sure it’ll go away.’ She could hear herself sounding one foot tall. ‘I mean – I’ll wash it – ’

Mrs. Kumar said, ‘Come. I will show you.’ She turned and left the bedroom, still carrying the sheet.

They went down two floors and into the basement. There was a sink there, deep as a well, cold, cracked and forbidding. A pipe jutted out from the wall. A pressure-valve perched at the end of it. ‘Here,’ said Mrs. Kumar, ‘here you will wash it.’ She dropped the corner of the sheet that she had been holding into the sink. ‘Wash now,’ she said, ‘it must not become…’ She searched for the word. ‘Stain. It must not become stain.’ There was an antique cake of laundry soap congealed into a tin soap dish on the rim of the sink. ‘See – there is soap – ’

She glanced up at Sarah, then turned again and left. What had the glance meant, wondered Sarah. There had been something there, something … She shook her head and the bushy mass of her hair shifted on the back of her neck, feeling comfortingly warm and familiar. Get this over with, she thought, just get it over with and don’t let’s think about it just now.

She held down the release on the valve. A stream of liquid ice gushed out, biting straight through the tender flesh of her fingers and deep into the bone. She flinched, wondering whether there was any point wetting the whole sheet. She picked it up and scrolled through it gingerly, looking for the stain.

It wasn’t easy to find, what with the all-over floral print, Faux Monet. Ersatz Klimt. But it was a blue-based design and the stain was there, finally. A single pale petal of dried, graduate-student haemoglobin amidst the heaving water-lilies. Sarah positioned the spot under the outlet and pressed the release. More Arctic water. She reached for the soap tray but it had become cemented to the rim of the sink. She hauled the stain-bearing area of the sheet over to the soap-dish and scrubbed the cloth into the soap, which was rock-hard with age. It was minutes before it grudgingly yielded up its suds.

Then she held the material between her numb fingers and scissored it back and forth rapidly, to work the soap into the stain. Wetted it again, just a little, enough to see that the petal was indeed fading. Scratched at it with her fingernail. Looked around for a brush, but there wasn’t one. The fine scum from the soap was under her nail now. A faint blush of brown in the scum indicated that the stain was shifting. Minute particles of her being, her discarded corpuscles, were detatching themselves from the cotton fibres of the sheet, tearing free and riding up on the skins of soap bubbles so fine that she could only see them collectively, as scum.

She held the cloth

under the stream of ice. The brown scum slid abruptly off the site of the stain onto that part of the sheet resting on the bottom of the sink. Damn! thought Sarah. She held the release of the valve down with one hand and tried to hold the sheet up so that the flow of water washed the scum clear of the sheet.

It was absurdly difficult. The sheet filled quickly with water, becoming heavy and unmanageable. There was a moment when she considered holding the cloth with her teeth so that the frozen lump at the end of her left arm could smooth away the traces of soap from the sheet while she held the valve open with her other hand. But she decided against it, ultimately. It would have looked ridiculous. And besides, she wasn’t sure that her teeth could support the weight of the sheet, now several pounds heavier as a result of the absorbed water.

Ultimately she draped the bulk of the cloth over her right shoulder, held the valve open with her left hand and used her right to smooth away the soap. The stain itself had faded to a memory, its edges slightly darker than its centre. But she rubbed it into the soap once more, flattened the cloth onto the palm of her left hand and scraped at it with the nail on her right thumb, scraped until it seemed to her that the blue of the underlying water lily was beginning to wear thin. Then, satisfied, she washed the scum away in the gelid water until all traces of soap had been obliterated from the sheet.

When she was done, she held the cloth up to look at it, stretching it between her two arms to do so. A film of water which had clung to the surface of the cotton gathered itself up into an icy rivulet which flowed straight into the warm space between her hair and her neck, down her back and into the divide of her bottom, resting only once it had reached right upto the threshold of her most private self. It was like a cold electric finger tracing the length of her flesh, invading her warmth, violating her with its icy impertinence. Then it fell away and dropped to the floor.

She shivered. Realized that her nightie had got soaked and that she was standing in a dark, unheated basement, half-swaddled in a wet bed sheet. There was something offensive and illogical about it all which she would have to examine and understand and file away. But not just now. Later.

She went to the laundry room by the kitchen. Mrs. Kumar was already there, bending over, stuffing a damp and faintly steaming wash into the round open mouth of the dryer.

‘Uh,’ said Sarah, ‘excuse me?’ Mrs Kumar did not seem to hear. ‘Mrs Kumar?’ The old lady straightened up slowly. ‘My sheet …’ said Sarah, indicating that she’d like to include it in the load going into the dryer.

For a moment it seemed as if Mrs. Kumar hadn’t understood what Sarah was saying. Then she shook her head, a quick bird-like movement. ‘No,’ she said, ‘no! Not here! Only down! In basement!’

Sarah said, ‘There’s no place in the basement – ’ But she had been in a hurry to get away and it hadn’t occurred to her to look.

‘There is place,’ said Mrs. Kumar and bent once more to her wash.

Sarah turned and went back the way she had come. Her mind was blank. In the basement, she looked around and saw that there was a light bulb with a dangling cord. She pulled on it and in the resulting light, saw that a potential clothes-line extended across the room.

She hung the sheet, turned off the light and went up two floors to the bedroom. Shut the door. She was shivering. She wrapped her arms around herself. What’s happening to me? she asked herself. She was shivering with anger, not cold. What am I doing here? she thought. What am I doing amongst … these people? There. It was out. The words that had been hovering at the edge of consciousness for three days now. These people. Deep and his mother. Indians. Not-us. Foreigners. Aliens.

But not him, she thought. Only his mother.

Or was it? After all, he had lived with his mother these many years. It had to have affected him. What would he say about the sheet, for instance? Would he find some excuse, some justification for his mother’s behaviour? Or would he see her, Sarah’s, point of view? And if he didn’t – wasn’t that the thing which made his foreignness a problem? The fact that, instead of automatically seeing her point of view, he would flip it over onto its back and expose its soft underbelly, expose it for just another cultural blinker. ‘Even you,’ he would say, smiling with his beautiful teeth, ‘have that Western bias which makes it difficult for you to see that there isn’t anything intrinsically bizarre about being made to wash your bloodstain out of the bedsheet in a freezing basement sink!’ And then he might cock his head to the side and say, ‘Remember the horsemeat?’

She bit her lip. The argument had started innocently. On their way up to Deep’s home from Cornell, they had driven past a meadow dotted about with Holstein-Friesians and she had nudged him. It had been a joke, nothing else. ‘Wanna stop?’ she had said. He had looked at her without comprehension. ‘You know,’ she had persevered, ‘stop by and say a prayer or – or something – ’ But he had still not understood. It had begun to seem too silly to explain. ‘Never mind,’ she had said, ‘it’s not worth going into.’ He had insisted, however. So she had said, ‘The cows, you know? We passed a meadow and it was full of cows and I thought …’ His expression had been so blank that she would have laughed except that she knew he got hurt easily. So she stammered painfully on. ‘Well, you know – I thought – since Indians worship cows – ’ But it had started to sound ghastly, even to her ears.

He had begun to nod in that quick tight way. ‘You think it’s funny, don’t you?’ he said, finally. ‘Just one more laugh-riot from the cosmic joke book – the joke book in which everyone who isn’t a Bible-thumping, beef-eating, baseball player is treated like a court jester. Everything we do, whatever we find sacred, is hilariously funny just because it’s different – ’ And then the final rebuke. ‘I thought you, at least, would understand.’

‘Deep,’ she had said, distressed. ‘You’ve got it wrong.’

‘What else can it mean?’ he said. ‘We’ve talked about this. I’ve explained it before.’ He paused and she could see the muscle in his jaw tensing. ‘About cows.’

She said, ‘Deep – it’s just that I saw them grazing and, and I – ’ She stopped. What had she thought? ‘I thought of a cathedral. I thought that maybe for someone who worships cows, a big barn must be like a cathedral is for us – ’ Was that really such an insulting thought?

He had said, ‘We discussed it just the other day. Didn’t you hear me? When I told you that it isn’t just any cow? That it is specifically the Indian cow?’

It had been her turn to look blank. ‘You mean, one breed?’ she had asked, astonished.

His face convulsed with annoyance. ‘Don’t be stupid!’ he said. His face worked, as he tried to compose an answer which would make sense to her. ‘It’s not a question of breed,’ he said, eventually, in a calmer voice, ‘it’s more subtle than that. In an Indian village, cattle are the foundation of life, an integral part of the family. Here? They’re just beasts! Milk dispensers! Meat!’

Sarah could feel a charge building up inside herself. Why are we talking about cows, she thought. Why aren’t we talking about you and me?

‘Do you understand any of this?’ he had said. ‘I mean – you look into the eyes of one of these animals here and you see nothing. Just a dull, stupid, unreflecting stare!’ His upper lip had lifted in scorn. Sarah couldn’t understand why or how it could matter so much to him. Then his expression had softened. ‘But – ’ he said, ‘you look into the eyes of an Indian cow and there – you see it. Consciousness! An Indian cow is a developed being. She has a mind, she has a life, she is a person – no, better than a person. A sort of living manifestation of the, uh, bounty, the giving spirit of nature.’ He looked at her, glancingly, as if expecting very little. ‘For the Indian villager, the cow’s milk provides food and income, its dung is used as fuel and the bullocks are a major source of draught energy. And on top of all that, they eat almost anything – they’re part of the garbage disposal system!’

He smiled slightly now. ‘Does it make sense now? Do you understand the difference?’

Sarah had nodded. ‘Yes,’ she had said, uncertainly, ‘yes, I think I can relate to what you’re saying.’ She had grown up on a farm, till she was eight. She fought down a vague irritation she felt at the way he had described American cows. How dare you insult our cows! she had wanted to say. But instead she had said, ‘We have that kind of relationship too, with horses – ’

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

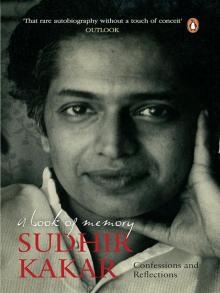

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory