- Home

- Sudhir Kakar

Indian Love Stories Page 2

Indian Love Stories Read online

Page 2

What kind of people were these, who like to sniff at each other like starved dogs? Shameless bastards! As if they would not strip you naked if they could. The other day the zamindar of Chakroad died – now doesn’t the chowkidar Haladhar’s hag of a wife sleep on the zamindar’s bed made of uriam wood? Doesn’t woodcutter Sukura’s wife puff away at the hookah scrounged from this cremation ground? Some people had even salvaged gold rings from the charred remains of cremated bodies – but no, no one kept track of those things. No one had the morbid curiosity to go and see how Haladhar’s spectre-like wife slept on the zamindar’s bed. The belongings of the dead were scattered in the shacks and shanties in and around the crematorium. Various opulent objects leered from these incogruous settings. Yet all eyes were only on this black box of hers!

Toradoi returned to her shack. She could see her sleeping children. Anyone could count their ribs. Their trousers hung loose like the hides of goats strung up in a butcher’s shop. But there, next to them, lay the wooden chest! Its very existence was a source of strength to Toradoi.

She caressed the chest with her hands. The bakul flowers, beautifully engraved on its sides, seemed quite real. She pressed her cheek to these flowers. After that, as on other days, she wriggled into the huge chest and lay there, leaving its cavernous mouth open.

Strange! Strange indeed! Revelling in the incomparable pleasure she felt, she lay inert for a long time in this chest which had been flung aside after it had been divested of its dead passenger. When she had scrounged the chest from the cremation ground she had to take out some bloodstained pieces of ice from it. She had almost forgotten about that. Toradoi wept.

After sometime, a police jeep roared past her hut. Usually no vehicles other than police cars passed this way. Were the certificates pertaining to the handing over of the bodies of people killed by gun-shot, in order? Was it true, as the chowkidar’s report would have it, that someone had come and burnt a bastard-child here without getting a ‘handover’ certificate? And what about the unregistered corpses? Such were the matters that drew the police to this area. Also, the flesh-trade of the prostitutes of Satgaon flourished here.

It seemed as if the higher the flames devouring the dead, the greater was the heat generated by the bodies of these prostitutes. Yes, there were so many things that the police had to attend to! So many matters that ensured a continual movement of police cars, that led to altercations between the police and members of the crematorium committee.

Toradoi woke up with a start at the sound of the police zonga.

Vermilion and flowers, meant for decorating the hair, lay scattered inside the chest. Strange! How had her very being become so inextricably entangled with this inanimate chest? She felt she was spending the night on the same bed with the ‘adored one’. This wooden chest bore the imprints of her personality: her hair-oil, vermilion. Last night she had again taken out her wedding blouse from the pile of tattered clothes, and put it on. It was the only article of her clothing which was still intact. Looking at her reflection in the mirror in the flickering light of a kerosene-lamp, she had combed her hair with frantic eagerness, as she had done ten years ago. She had not even felt the comb grate against the bones on her shoulder and neck. In those days she had hardly known of the existence of bones, buried under the abundance of pliant flesh. Now people said that she was one of the numerous living skeletons subsisting on the cremation ground.

Was anyone looking?

These days people peeped through crannies and gaps between doors and windows and walls. Her boys, now sleeping peacefully, had complained that people spied all the time.

‘Shame, Shame! Sleeping in the box that carried the dead! Throw it away!’ the voices seemed to say.

Toradoi snuggled into the chest. This experience was unique.

Suddenly, someone gave a massive kick to the door. Startled and flustered, Toradoi got up. Straining her ears, she heard the booming voice of her brother Someswar who worked in the police.

‘Toradoi! Toradoi!’

As soon as Toradoi opened the door a man dressed in police uniform burst in. He was sturdily built, and with an imposing moustache. He wore a pair of huge, ungainly boots and carried a sizeable stick.

‘I haven’t been able until now, to find the time to see how you are. Today my duty is in these parts. That woman from Satgaon has virtually set up shop here. It seems virtue is totally extinct. Only the other day Barua died and his two sons brought his body to the crematorium. While one was busy performing the last rites, the other gave everyone the slip and was in that prostitute’s room in a twinkle. Really, we have fallen on evil days!’

Suddenly he gave a gasp and retreated a few steps as if he’d seen a snake. Someswar gaped at the massive, elaborately decorated wooden chest. Going closer he tapped it with his stick. Then he walked around it. Finally, he knelt down by its side and taking out a handkerchief rubbed his eyes. The man who had rushed in like a storm a few moments before, now resembled a dejected and defeated soldier. He looked at Toradoi and asked in a broken voice, ‘Is there some water in the house? Get me a glass of water, will you?’

He gulped down the water and then, said with his head downcast, ‘What I heard is true, then. Saru Bopa’s corpse travelled here in this chest. I accompanied the family part of the way from the airport. Yes, this is that chest, alright.’

Casting a level and direct gaze at Toradoi, he said, ‘Don’t think I don’t remember that you worked for them. Everyone knows what a great help you were when Saru Bopa’s father, the Thakur, was ill. Washing all those clothes stained with blood and pus. And Saru Bopa?’ Someswar’s voice grew heavy with emotion. ‘He was so fond of you. Wasn’t that the time when he was bent on marrying you? What a fracas there was in the Thakur’s household over this! Then came the hasty transfer to Upper Assam – and then – the accident.’

Toradoi asked suddenly, ‘What killed him?’

‘A jeep. What a fine figure of a man he was! After removing the bloodstained pieces of ice I helped hoist his body onto the funeral pyre. With these two hands of mine. Fresh young blood on my hands …’

Looking at Toradoi standing like a statue, he could not complete his sentence. The big, black box with its open mouth was like some mysterious cave, separating and alienating the two of them.

Suddenly Someswar stood up and bellowed. There was a hint of the theatrical in his gesture. ‘Toradoi, the days of the sahebs marrying the daughters of labourers are gone. The grass now grows tall over the bones of Jenkins Saheb who married a labourer’s girl. The big saheb’s son, Saru Bopa, vowed he’d marry you. But could he do it? Did he succeed in taking you away from this hovel and giving you a place in a house with a tin-roof?’

A sigh that seemed to wrack her whole being, escaped Toradoi. ‘Only because he couldn’t marry me did he remain a bachelor. Twelve whole years have gone by – probably he would not have married at all.’

The huge constable glared at Toradoi. Beating a staccato note on the floor with his stout lathi he stood up, cursing Toradoi in a deep, rumbling voice. ‘You are still as much of an idiot now as you were when you gave yourself completely to the Thakur’s son. I work in the police, so I have heard everything and have come prepared.’

Toradoi looked helplessly at her brother. She had managed to salvage something precious from what had once been. Would her brother deprive her of even that?

By this time the sleeping children had got up. The three of them huddled together. They looked like phantoms from the cremation ground.

Someswar started rummaging in his pocket. The boys thought he was going to come up with something for them, just as the man did who always waited for their mother. After all, he was their uncle, though he had not once come to inquire after them when their father went to jail.

The three creatures continued to stare at Someswar. Toradoi could almost hear her own heartbeats.

Someswar dug out a bundle of letters from his pocket and flung them in Toradoi’s face. ‘Here, take

these wedding cards of his,’ he declared. ‘Seeing the way things are going, I came prepared. Saru Bopa was not planning to stay an eternal bachelor because of you. His wedding had been fixed. Wedding cards had also been printed. Read them. Read them! In fact he was on his way home to get married when the accident happened. Read them and pray for the peace of his soul.’

As he was about to rush out of the room, he suddenly noticed the boys clinging to their mother. He searched for some coins, but his mind was already on other things. Toradoi could hear him mutter, ‘If I can catch that woman who peddles her body to mourners, or catch Haibor red-handed, I can make this trip worthwhile. That bastard Haibor passes off worn-eaten wood as sal wood.’

Taking out a fistful of coins, Someswar thrust them into the eager hands of the boys and left the way he had come. The moment their fingers closed around the coins, the half-starved urchins streaked off to the nearest shop.

Toradoi remained rooted to the spot near the pile of wedding cards. She reached out for the cards like someone who groped for the bones of the dead among the ashes of the crematorium.

Yes indeed, these were invitations to a wedding.

Toradoi did not venture out for many days.

Tormented by unbearable hunger, her two boys were driven to beg from the people who came to burn bodies. Someone had tied a gamoccha, which must have been worn by a person performing last rites, around the younger boy’s head. The boys had managed to scavenge two empty liquor bottles from the cremation ground. These they had washed, filled with water from the well, near the statue of Yama astride a buffalo. This they drank to quench their hunger. The neighbours knew that Toradoi’s hearth was cold.

The big black chest lay with its mouth yawning open, like the cavernous mouth of hell.

Under the hijol tree Haibor kept up his unceasing vigil.

One morning, while the gloom of the night still clung to the sky, Toradoi and her two sons could be seen dragging the wooden chest towards the cremation ground. Toradoi put the box on the spot where the bastard-child had been controversially burnt and set fire to it.

The bul-buls on the hijol tree started chirping noisily. The sun rose above the Brahmaputra. Wreaths of violet and brown clouds clung to it, making it look like the pinched and pale face of a hapless prostitute, blushing at the thought of having to spend time with an unwanted stranger. The clouds seemed to lay bare the strange combination of helplessness and indomitable strength on this face.

The cinders of the burnt-out chest were scattered all over the place. In the morning sunshine they resembled the hide of a freshly butchered goat, spread out on the earth to dry.

Toradoi came out of her shack.

She wore no chadar.

The man who always stood under the hijol tree was not there.

Translated from the Assamese by

PRADIPTA BORGOHAIN

THE HOUSE COMBUSTIBLE

Subodh Ghosh

hat must be the ferry train just arrived at Rajpur Junction, out of breath, in the cold drizzling darkness. Probably it came from the direction of the Ganga. A little while ago a ferry steamer had disgorged a crowd of people who had crossed the river, and the sound of its receding whistle could still be heard as it headed back to the other bank.

The engine of the train, standing close to the platform, was letting out steam. The attendant of the first-class waiting room dusted the few pieces of furniture and the mirror with a towel, and the cleaning man removed, with a wide sweep of his large broom, what litter there was on the floor.

Although the ferry train was small, not all those who travelled on it were poor Santals. There were always a few passengers on it who travelled first-class; perhaps an owner of some sugar factory in Katihar or a manager of some tea garden returning from Darjeeling.

However, the two passengers who arrived tonight and headed for the first-class waiting room for shelter had no connection with any sugar factory or tea-garden. The first to enter the waiting room was a Bengali woman. Her walk over the platform in the drizzle was brisk, and she was followed by a porter who was carrying her luggage on his head. She wore an overcoat of Kashmiri woollen material, small ear-rings and her hair was tied neatly in a Western-style bun.

The next person to enter the waiting room, a Bengali bhadralok, was also followed by a porter, carrying heaps of luggage. He wore a pair of spectacles and was dressed in the traditional Bengali style, with a shawl wrapped round him.

A man and a woman who had travelled on the same train now took shelter in a waiting room that is the only relation between them – if that can be called a relationship. One would perhaps wait here for a couple of hours while the other wait for an hour or so, to catch their respective trains.

Strangely, however, both were startled as soon as they looked at each other. Then they were unusually quiet, but looked somewhat embarrassed, annoyed, even apprehensive as though they found themselves in the dock of a court which they had earlier fled. Drops of water shone on Madhuri Ray’s overcoat; Satadal Datta didn’t remember to wipe his spectacles either.

But they were in the waiting room of Rajpur Junction, not in any court of law; there was no judge here, no pleader, no witnesses and no gathering of curious onlookers around them. There was no one here to ask them embarrassing questions. However, when they found themselves so close to each other in an undisturbed situation it was intolerable for them and both longed to get away from each other.

Madhuri’s luggage was heaped over a bench and Satadal’s on a table in a corner.

Satadal moved to the door and called out for the porter. He had decided to move out of the room with his luggage. But where to? He didn’t know. Some acute embarrassment made him leave the room. Perhaps he would go to the common waiting area where there was little light and no furniture, but at least he wouldn’t have to face a vivid and painful shadow from his past.

No porter responded to his call but instead an attendant came in and said, ‘Yes, sir?’ and stood there, waiting for Satadal to tell him what he wanted. Satadal took a few steps towards the door, looked out – it was still drizzling – stepped back, as if considering what to say. He looked visibly annoyed with himself. It was quite unnecessary to be so disturbed by the presence of someone in the waiting room, there was no point in succumbing to some baseless nervousness. The attendant meanwhile mumbled, ‘Would you like me to do something, sir?’ ‘Get me some tea, please,’ Satadal blurted out as he drew a chair up to the table.

On the other side of the room, Madhuri Ray took off her overcoat and put it down on the bench, from which she pushed aside her luggage to make room for herself to sit more comfortably.

Two persons, Satadal Datta and Madhuri Ray, were waiting for their trains at the waiting room of Rajpur Junction. There was nothing common between them any more except the fact that they were both waiting in a railway waiting room. There was now no relationship between them – not now, not for over five years; but there had been before, and that too for seven long years. That relationship began some twelve years ago when Madhuri Mitra, then a pretty girl, was a friend of Satadal’s sister-in-law, his brother’s wife. They met at Ghatsila in the month of Falgun, when the air there gets heavy with the smell of wild flowers. It was there, one afternoon when Satadal and Madhuri had gone out for a walk. And that was how their relationship began. Within a year, their acquaintance developed into intense love for each other. And their love was formally acknowledged through the registration of their marriage. However, within seven years, that bond of love became very weak, and they both agreed to legally separate through divorce.

Somehow it became clear to both that they did not love each other any more. Mentally they had drifted apart, and both of them, had good reason to get away from each other. They felt no urge to go on acting the expected role of husband and wife for the benefit of people around them, and so they separated without any fuss.

The love that was formed and matured in the fragrance of mango blossoms one Falgun did not last seven Fal

guns. One day Satadal had to go to Bhubaneswar for a week to supervise some work connected with archaeology. While he was packing his clothes in a suitcase in one room, Madhuri was reading a book in another. She did not come in even once till the moment of Satadal’s departure. It was a bright winter morning, the sun came through a window flooding his room, but Satadal felt as if everything was quite pointless.

But that morning of Paus alone was not to be blamed. A Sunday afternoon in Chaitra of that very year also played a cruel trick. As on other Sundays, Madhuri was waiting, dressed up to go out for a walk. When in the adjacent room Satadal was busy preparing a sketch of a temple in the Chalukya style. He completely forgot all about the walk. As she looked out of the window, the reddish glow of the sky due to the setting sun appeared to her to be too short and a bad omen, for it would soon be all dark. She wished the sun would go down quickly without indulging in further antics.

Some similar happenings, one after another, made them both see that their love had withered away, or, perhaps there never had been any love between them – these indications were surfacing every now and then. Who knows which was true? Perhaps they could have known if they tried to; maybe they knew, or they didn’t. In any case, whether they had known or not, neither ever blamed the other. Both kept quiet even if they realized what had happened, or perhaps deliberately avoided making an effort to know.

It was even possible that each had secretly fallen in love with someone else. Anyway, the odd Falgun month of Ghatsila had lost all its charms. Perhaps the pain of the loss of that attraction pushed them further apart, making them seek solace in new companions, new relationships. Whatever that might be, neither of them had any regrets. Either both had made the same mistake or both had done the right thing. Neither could blame the other.

And they didn’t. But they kind of hated each other. They couldn’t forgive and forget. However, nothing showed outside in their behaviour. But a time came when it was just not possible for them to keep these emotions suppressed, and then they drifted apart. There never was any argument between them. They managed to get a legal divorce easily – putting a formal end to their seven-year-long relationship.

Death and Dying

Death and Dying The Indians

The Indians The Crimson Throne

The Crimson Throne Indian Identity

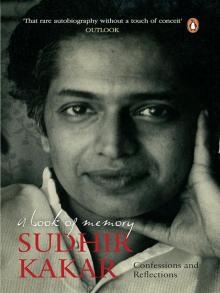

Indian Identity A Book of Memory

A Book of Memory